(Adapted from 100 LAST Orchestration Tips, planned for release in late 2026)

Despite claims of its obsolescence, C clarinet is still employed in a limited way by section players and soloists. However, it is by no means an escape valve for anti-transposing composers.

As a social media moderator of orchestration topic for the past 15 years, I know that from time to time certain claims will arise, such as the brash yet inexperienced proposition that B♭ and A clarinets are completely unnecessary, because there already is a C clarinet which simplifies everything. Digging a little deeper, it always turns out that the claimant’s main attraction to the instrument is its lack of transposition. And then of course, the experienced clarinetists are bound to jump in, pointing out the how the instrument is outmoded – with some comments even claiming that they’re functionally extinct.

Two opposing misperceptions are at work here: that the C clarinet should be used (or revived) purely because some composers don’t want to stretch their brains a little to learn the fairly simple yet necessary work of transposing at sight; and vice-versa that the C clarinet is never played anymore and we should all just forget about it because it’s a failed proposition. Both viewpoints are patently untrue – not that I blame anyone for having them – and all that’s required is a little knowledge about the instrument itself: why it was developed, how it was used in the Late Classical/Early Romantic periods, and why it was eventually abandoned. But on top of this, why it still appears in the performances of works from those periods.

The thing to understand about the clarinet’s emergence is that it happened at a time when symphonic/operatic music was making rapid strides in its development, in both orchestration and intellectual complexity. As a new resource of timbre, it offered unique opportunities for adventuresome composers like Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and Weber. And yet we should be aware that keywork was not yet anywhere close to modern systems at the beginning – which is why we see early clarinets composed in so many different keys; E♭, D, C, B♭, A, and the basset horn in F.* This ensured that players would have the easiest possible time playing passages written in any given key of a movement or passage – though to be perfectly honest about this, most earlier clarinet parts were fairly straightforward, with only the occasional concerto-level virtuosity required of specialist performers.

But there was more at work here than ease of fingering. The length of bore played a huge role in the quality of tone to be expected from any particular model, especially with regard to their individual registers. An E-flat clarinet might have a bright, piercing clarino register above, but a rather shallow and unconvincing chalumeau register below. With more than twice the bore length (due to its extension down to low C), the F basset horn would deliver a beautifully rich, solid chalumeau register – but a somewhat compressed clarino register, similar to the less bright tone of higher viola pitches. In the exact middle between these two extremes were the B♭ and A clarinets, representing a tempered clarino register and a rich yet not too solemn chalumeau.

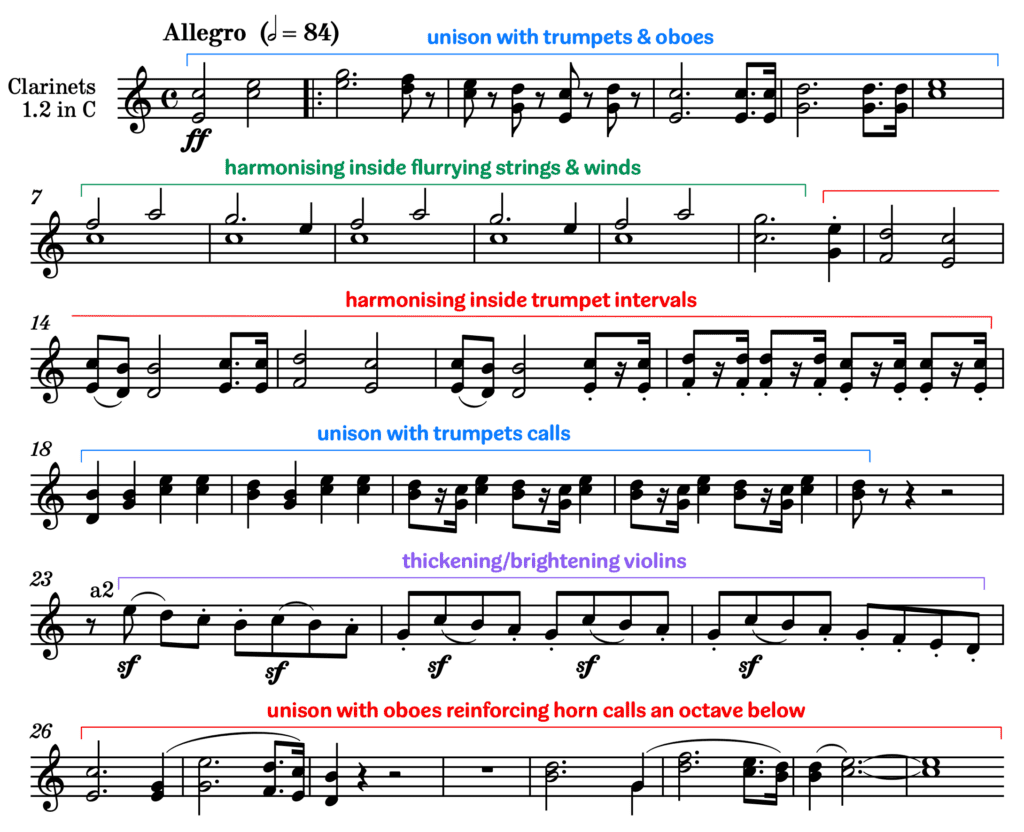

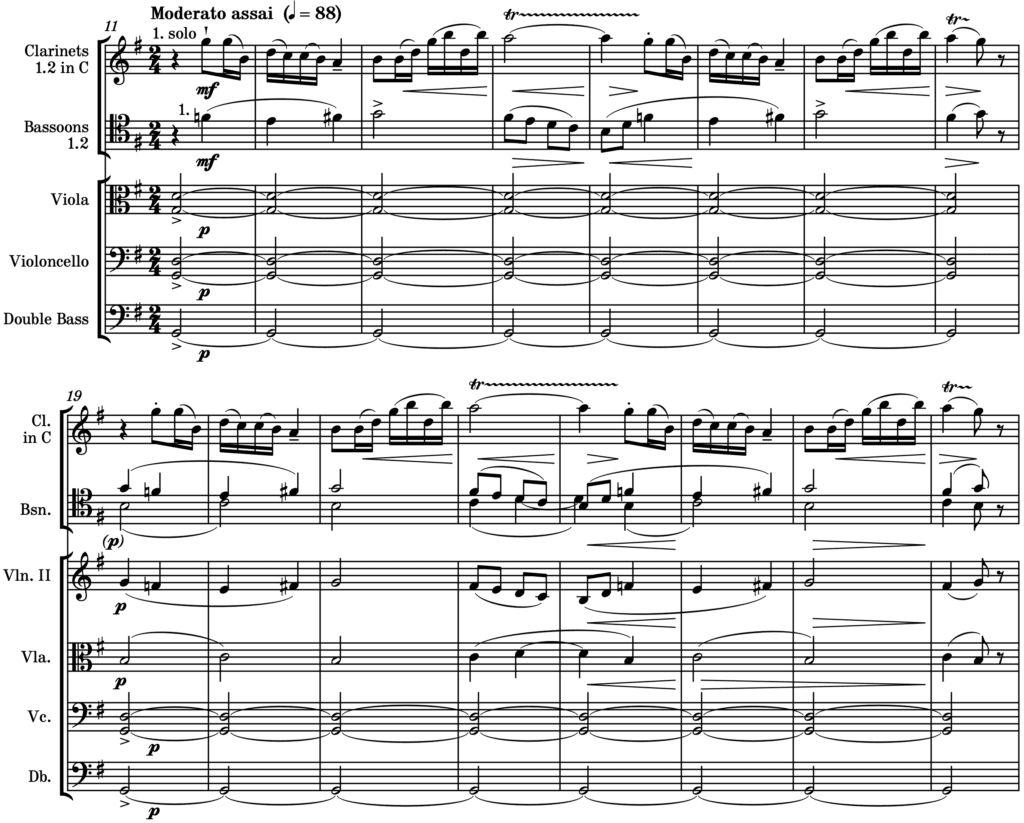

The C clarinet, on the other hand, had a brighter tone approaching the E♭ – and yet with much more muscle. Gevaert described it as “dazzling to the point of harshness.” Composers of the day would of course assign it to pieces in the key of C for which it was built; and also G in some cases. But looking over the repertoire, we see a few caveats added onto the equation, the most important of which would be that the music’s character would tend toward a more powerful, assertive expression. For instance, in the fourth movement of Beethoven’s titanic 5th Symphony, a very noteworthy appearance, two C clarinets state the opening theme in unison with trumpets and oboes, easily contributing a clear, intense colour inside this powerful combination. From there, Beethoven scores his pair of C’s in a way that’s very aware of their power: harmonising inside the flurrying strings and winds, playing an octave above the trombones; then descending to play harmony and harmonic rhythm inside the trumpets like two additional trumpets; then unison with trumpet calls under more swirling upper strings and winds; thickening and brightening 1st and 2nd violins; and then unison with oboes reinforcing the horn cals an octave above. It’s all a tremendously exciting moment, made all the more powerful by the use of C clarinets.

Link to full score+audio examples on YouTube in my announcement video.

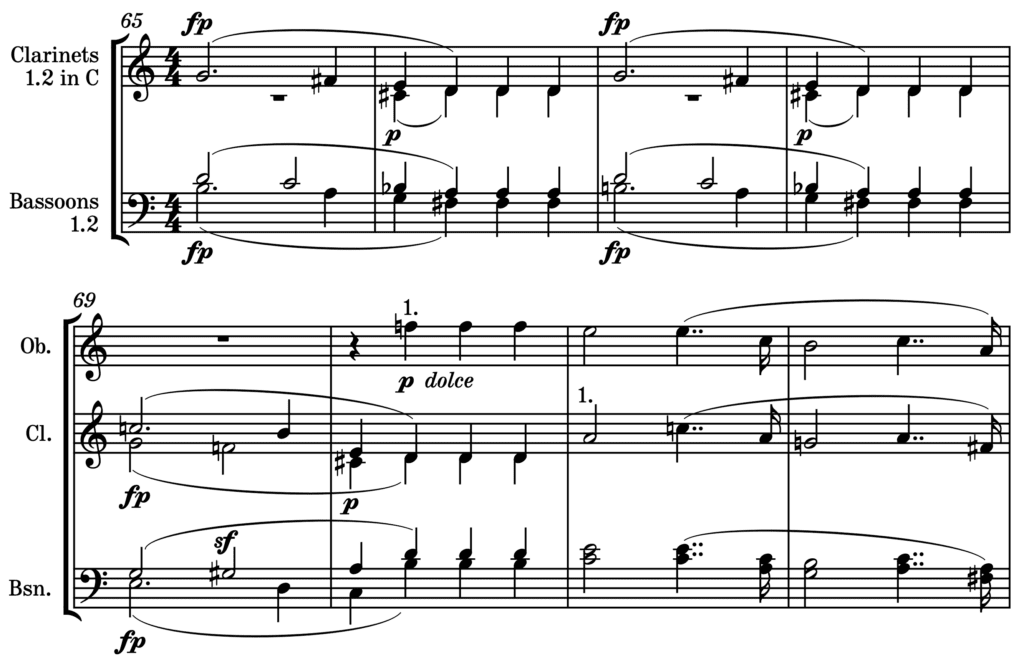

Further on, Beethoven allows the clarinets to speak out more on their own, albeit cushioned by doubling from violas and cellos, yet highly spiced with their intensely reedy quality. Here’s where modern B♭ clarinets are at a disadvantage in expressing Beethoven’s intentions, as they cannot match the blatant brightness of the C clarinets over the same sounding pitches, evoking the common-man simplicity that he heard and admired in the folk band playing which he’s emulating here.

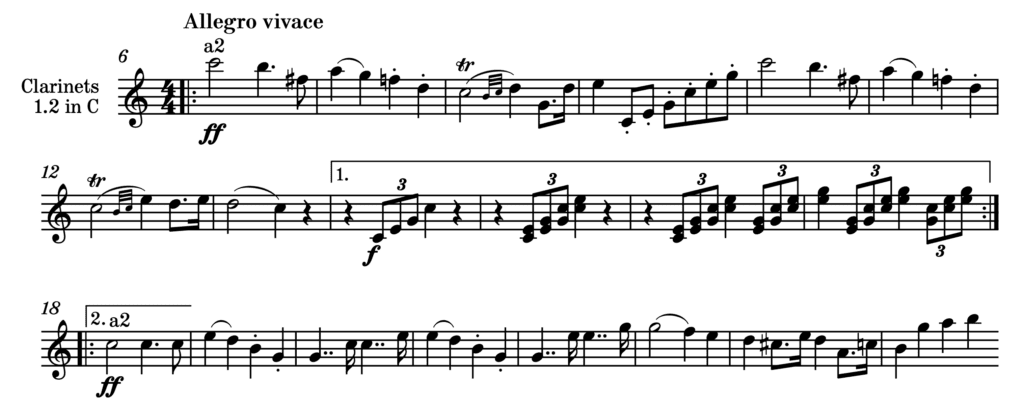

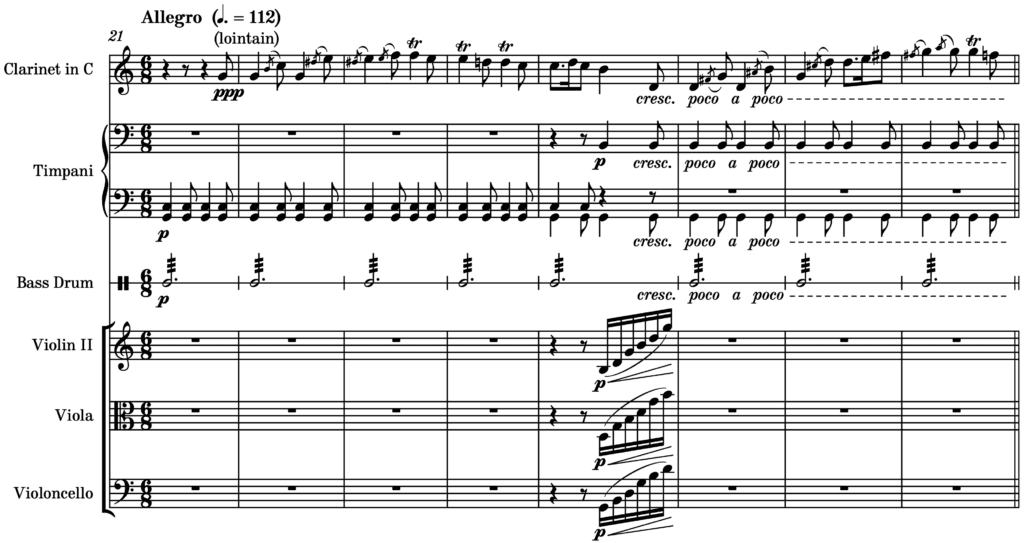

Mendelssohn scored another great example of rustic, high-energy C clarinets in his incidental music to A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Though their parts mostly double the oboes, in unison with or an octave below flutes, they still imbue the melodic line with an intense, hard brightness. This will speak with overpowering conviction on those high C’s.

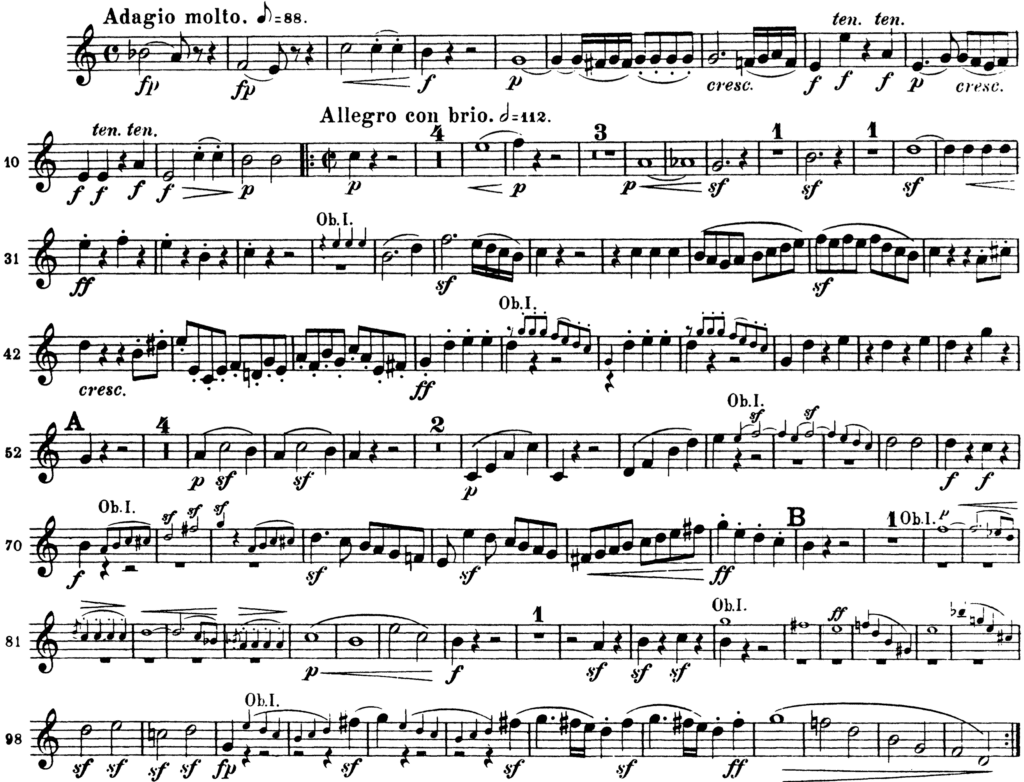

Mendelssohn’s high C’s here notwithstanding, the more typically employed range of the C clarinet in those times covered around an octave-and-a-half from D4 to G5: avoiding the lowest range of the chalumeau and the brightest notes of the clarino (and leaving out the altissimo register altogether). This logically kept the C clarinet’s less appealing characteristics of shallow low notes and lighter high notes to a minimum, while pushing its stronger, richer range to the forefront. The 1st clarinet part from Beethoven’s 1st Symphony bears this out, with notes sticking mostly to the staff between D4 and G5. The occasional A5, C4, A3, and G3 make appearances, as does a nice popping C6 at the end. Admittedly, the 2nd clarinet makes more use of its lower range, but usually in harmony with the 1st clarinet or within a greater texture.

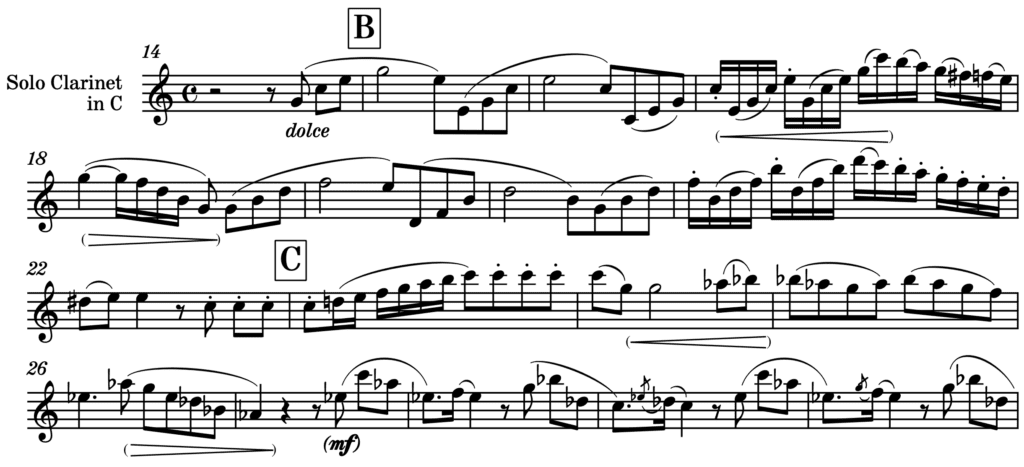

So how popular was the C clarinet? It appears that from the start, it was considered a lesser member of the complement. That’s not to say that it was unusual or rare by any means. The list I’ve provided at the bottom of this tip shows that it was employed in many significant works. But composers of distinction appeared to be well aware that it was not by any means as universal a member of the clarinet family as the B♭ or A models. Due to its dramatic character, we see it in many theatrical and operatic scores; such as Mozart’s grander operas, Haydn’s The Seasons, and Beethoven’s incidental music to King Stephen, overtures like Consecration of the House and Leonore no. 2, his opera Fidelio, and ballet The Creatures of Prometheus. Dramatics aside, though, the C clarinet also performed the requisite duties of a section player, in symphonies such as Haydn’s 100th; Beethoven’s 1st, 5th, and 9th; Schubert’s 1st, 3rd, 6th, 7th, and 9th; and Mendelssohn’s 2nd and 5th. In many of these works and more, the C clarinet shared the score alongside its more familiar sisters the B♭ and/or the A, swapping between movements and scenes as necessary, usually following the key signature but often brought into the action for its brilliance of timbre. Several soloistic works survive to this day that help illustrate the C’s unique qualities, such as Vanhal’s Clarinet Sonata, Dimler’s Quintet in C, and Böhner’s Fantasy & Variations for Clarinet & Orchestra. But Rossini’s Variations for Clarinet are probably the most well-known, and the orchestral version reveals a solo part for C clarinet, plus two section clarinets also in C. Rossini capitalises on the C clarinet’s punchy, piping qualities, and sticks almost entirely to the clarino register and the throat tones, plus a couple of high D6s. This is almost always played on the B♭ today, to the point which a B♭ transposing part is supplied on IMSLP under the mistaken title of “Clarinet solo (C)” – but I feel this misses the bright, sassy quality of what Rossini intended.

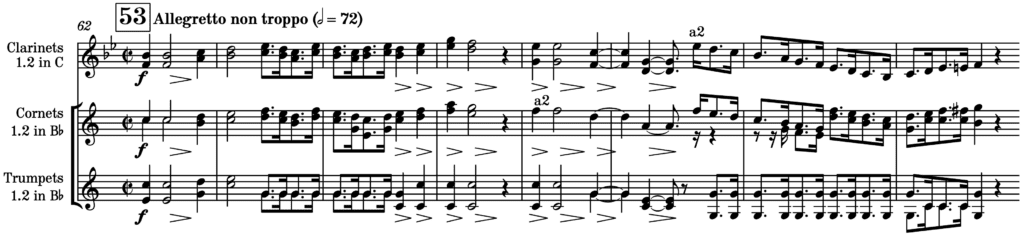

As the craft of orchestration started to evolve forwards from basic colouration and interactions of players developing themes, toward a more refined and grandiose command of colour and texture, the perception of a C clarinet’s properties became more specific and less integrated alongside the B♭ and A. For instance, in Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, C clarinets are scored in the B♭ fourth movement’s “Marche supplice” exactly because of their more penetrating brightness alongside cornets and trumpets. That could be the only justification for withholding B♭ clarinets in this context considering the key.

Later on in the 5th movement, Berlioz uses the C clarinet to embody the mocking laughter of his fantasy lover who has become a witch at the black sabbath held over his grave. Here, the more shallow, piping quality of tone is at a premium, with the clarinet’s very exposed voice cackling across that same choice range of D4-G5. Later on in the same movement, the E♭ clarinet will echo the same passage even higher and more shallowly – but here in the first statement, we at least hear a more balanced, stronger sound, for all its leanness. This extreme exposure of the C clarinet’s character was probably completely alien to the audience of the time, regardless of the appearance of the instrument in many other less blatantly picturesque works.

Symphonie Fantastique exploded upon the world from its first two performances in the early 1830’s. By the next decade, advances in keywork like the Boehm and Albert systems improved the technical fluency of the standard models of B♭ and A to such a degree that the C’s use in covering C major sections of operas and symphonies became less and less justifiable – at least to the players themselves, who might well just play any given C part on their B♭ instrument as a matter of course. Italian and French opera composers certainly played a role in this shift, with many of their clarinet parts written in C, leaving to the players to choose whichever model might seem most appropriate. For a working clarinetist of the era, that model might well be the B♭ more often than not, covering every key on the left side of the circle of 5ths, and even C and G. The A survived due to its practicality in sharp keys, but the C slowly waned.

In the list below, you’ll see the highest concentration of C clarinet works and their composers in the early part of the century – dwindling more and more until we see a only few works by Berlioz and Mendelssohn in the 1840s. In 1843, Berlioz was to write in his Grand Treatise on Instrumentation, “The tone of the Clarinet in C is harder than the tone of the B♭ and has much less charm.” Four decades later, Gevaert was to affirm in his 1895 New Treatise on Instrumentation that the C clarinet “…has been completely abandoned in this country” – though Richard Strauss in his 1904 revised edition of Berlioz’s Grand Treatise insisted that “The clarinet in C is indispensable for certain pieces of brilliant character…It is also preferable for passages demanding brighter colours.” Strauss was to back this up over the coming decade, helping to reinvigorate the C clarinet in the postromantic era with Der Rosenkavalier and Alpensinfonie, as his friend Mahler had already done in his 1st, 2nd, and 7th symphonies.

But one cannot bring up Mahler’s use of the C without touching on another role that it plays – that of folk music. As an instrument in C, it can easily cover any kind of part originally scored for voice, oboe, trumpet, violin, and flute. And its brighter tone helps lead small wind groups with ease. So as its use may have declined in concert and opera circles, it started gaining ground amongst folk players. In my list, you may have noticed Smetana’s opera The Bartered Bride, composed in the late 1860s during a time in which C parts for clarinet probably were played on B♭ or A models (as mentioned above). But in this case, the usage (throughout the entire opera) is entirely intentional. Of course its bright colour is particularly useful with regard to Smetana’s tone-painting, and the terrific energy of the overture – and yet it’s in the opening of Act I that his intention is revealed, as he scores a beautiful folk melody in chorale with two bassoons. From this point onward, the clarinet serves a reference back to those folk roots that inform the culture of this opera.

And this just leads back to Mahler, who also saw more potential in the C clarinet than just its brightness of tone, and also hailed from Bohemia just like Smetana – and yet from Ashkenazi roots – resulting in the charming klezmer-influenced breaks in 1st Symphony. In point of fact, the Albert system C clarinet appears to have been the instrument of choice for klezmer bands of that time; and Mahler brings this to life beautifully.

Over a century later, where does that leave us? Well, contrary to Strauss and Mahler’s hopes, the C clarinet didn’t really make much of a comeback, and remained a curiosity – and with time, an ever more expensive proposition for a model of the same level as a professional clarinetist’s top-of-the-line B♭ and A pair. Recently, many smaller instrument builder’s shops are offering more reasonably priced instruments, often with many of the problems absent that have plagued some C instruments in the past. So there has been a growing contingent of pro players who own C clarinets in order to more authentically perform many of the works on that list below. Every time I hear someone claim with total assurance that “The C clarinet doesn’t exist anymore,” I think of the many times I’ve heard those works from pro and semipro orchestras using the supposedly extinct instruments perfectly alive and well, thank you very much. Especially in the case of Symphonie Fantastique, which I’ve been assured is quite fun (if challenging) to tackle on the instruments for which it was intended.

And yet, before you rush over to your workstation and start composing your next masterpiece including C clarinet, you have to ask yourself why you think it’s necessary. Because every reason has a valid counterargument. The first is brightness of colour. While the C clarinet is naturally brighter than the B♭, that doesn’t mean that the latter can’t also play brightly and perkily, even to the point of aggravation, in its clarino register. And of course, if all you really want are piercing high notes, then the E♭ is already built for that, and far easier for the vast majority of section players to get their hands on if they don’t already own one. This especially goes for the chalumeau register; if you really want that shallow, hollow lower sound, then the E♭’s quality in that regard is much more pronounced.

But no, let’s say you’ve fallen in love with the specific sound of the C, and you absolutely must have that timbre because you know in your heart that your need outweighs my previous warnings. Well and good. So go listen to C clarinet solos, many many of them in a row. If you’re like the average listener, you’ll notice that while there are thrilling aspects to that sound, it does tend to use up part of a listener’s stamina. How long do you want to maintain that level of intensity to prove a point, let alone make an artistic statement? And furthermore, what kind of C clarinet writing will justify its use? You may have to strike a keen balance between featured lines and solos as opposed to more textural playing. Too much of the former may tire the audience – too much of the latter may fail to justify any effort on the player’s part to accommodate the effort of bringing a C to the gig.

Undeterred, you address all these concerns; finding players in your client orchestra who are more than keen to play your clarinet parts on their C instruments (somewhat unlikely, yet an absolute prerequisite); and they have models in good repair, plus vast experience with them; and you feel you’ve justified the use with a good balance of ensemble scoring and solo breaks that really bring out the soul of the instrument. What’s more, you go on to a terrific premiere that has the crowd raving.

The honest truth is that your piece is in danger of never being played again – because you may feel so justified by your care in sorting the details that you assume all future orchestras will be equally accommodating. If only it were so. Now is the time, if you haven’t done so already, to go through your clarinet parts and adapt them to alternative parts for standard B♭ and/or A tunings. And while you’re at it, mark the availability of these alternate parts right in the full score, so that the conductor reviewing your work for a possible performance doesn’t close the page and chuck the score in the return pile. Any little extra ask like that can immediately end the conversation, unless you show them that there’s nothing worth worrying about in terms of logistics for your work to be programmed.

But when it all comes down to it, if your ultimate motive for scoring C clarinet arises from any kind of anxiety about transposing the instrument, then just stop now and change your plans. Today’s composers can score their works entirely in concert pitch, and then either release the score in C with the parts transposed, or change the score at the click of a mouse to transposing. There is simply no reason any more to reject the B♭ or A clarinet in favour of the C simply because of problems understanding transposition.

Furthermore, it’s probably not the greatest idea in the world to score for C clarinet if it’s your first-ever experience writing clarinet parts. Any kind of specialist instrument really deserves to be approached by a composer with a great deal of experience and insight about the standard model of its family – in this case, the B♭. And perhaps with enough time spent learning the awesome capabilities of that basic workhorse, which I feel far outstrips any other member of the clarinet family in its potential, you won’t feel the need to score for the C at all. I certainly haven’t yet, after 5 decades as an orchestral composer. But I won’t turn down the offer if it arises.

*Basset models were essentially clarinets that added a “basset” (“little bass”) extension to the lower range of the clarinet, reaching from the normal lower limit of written E3 down a further 4 semitones to a written C3. So basset clarinets could be in any given key as needed, such as the basset clarinet in A for which Mozart composed his Clarinet Concerto, K. 622. While this latter instrument has made a comeback in recent years, realistically for the purpose of playing the Mozart as it was intended and little else, other basset models were long ago abandoned, with the exception of the most commonly known basset horn in F barely hanging on until its revival in the late Romantic era.

Works including C clarinet:

Beethoven:

- Cantata on the Accession of Leopold II, 1790

- Cantata on the Death of Joseph II, 1790 (C & B♭)

- Symphony no. 1 in C, 1800

- Piano Concerto no. 1 in C, 1800

- Creature of Prometheus, 1801 (C, B♭, & A)

- Triple Concerto, 1804 (C & B♭)

- Leonore Overture no. 2, 1805

- Piano Concerto no. 4 in G, 1806

- Mass in C Major, 1807

- Symphony no. 5 in Cm, 1808 (C & B♭)

- King Stephen, 1811 (C, B♭, & A)

- Wellington’s Victory, 1814 (C & B♭)

- Namesfeier Overture, 1815

- Fidelio, 3rd version, 1815 (C, B♭, & A)

- Consecration of the House Overture, 1822

- Missa Solemnis, 1823 (C, B♭, & A)

- Symphony no. 9 in Dm (C, B♭, & A)

Berlioz:

- Waverly Overture, 1827

- Messe solenelle, 1824

- Symphonie Fantastique, 1830 (C, B♭, A, & E♭)

- King Lear Overture, 1831

- Lélio, 1831 (C, B♭, & A)

- Benvenuto Cellini, 1838 (C & B♭)

- Le Corsaire Overture, 1844

- Damnation of Faust, 1845 (C, B♭, & A)

- Te Deum, 1849 (C, B♭, & A)

Böhner, Fantaisie & Variations for Clarinet & Orchestra, Op. 21, 1814

Devienne, Three Sonatas for Clarinet & Cello, 1790s(?)

Dimler, Quintet in C, 1797 (clar., bsn, str trio)

Haydn:

- Symphony no. 100 in G, 1794

- The Seasons, 1801 (C & B♭)

Mahler:

- Symphony no. 1, 1888 (E♭, C, B♭, A, Bass)

- Symphony no. 2, 1894 (E♭, C, B♭, A, Bass)

- Symphony no. 6, 1904 (E♭, C, B♭, A, Bass)

Mendelssohn:

- Symphony no. 5, 1830 (C & B♭)

- The First Walpurgis Night, 1832 (C, B♭, & A)

- Israel in Egypt, 1839

- Symphony no. 2 in B♭, 1840 (C, B♭, & A)

- Antigone, 1841 (C, B♭, & A)

- A Midsummer Night’s Dream Incidental Music, 1844 (C, B♭, & A)

Mozart:

- Abduction from the Seraglio, 1781 (C & B♭)

- Don Giovanni, 1787 (C, B♭, & A)

- Così fan tutte, 1790 (C, B♭, & A)

- The Magic Flute, 1791 (C, B♭, & A)

Pleyel, Concerto for Clarinet (or flute or cello) in C, 1797

Reicha, Wind Quintet in C, Op. 99, no. 1, 1819

Rossini, Variazzioni di clarinetto, 1809 (C clar. solo plus orchestra inc./2 C clars.)

Schubert:

- Symphony no. 1 in D, D.82, 1813 (C & A)

- Symphony no. 3 in D, D.200, 1815 (C & A)

- Overture in the Italian Style, D.591, 1817

- Symphony no. 6 in C, D.589, 1818

- Overture in E minor, D.648, 1819

- Die Zauberharfe Overture (Rosamunde), 1820

- Symphony no. 7 in E, D.729, 1821 (C & A)

- Symphony no. 9 in C, D.944, 1825-28 (C & B♭)

Smetana, The Bartered Bride, 1866-70

Strauss (R.):

- Der Rosenkavalier, 1910 (E♭, C, B♭, A, Bass)

- Alpensinfonie, 1915 (E♭, C, B♭, Bass)

Vanhal, Clarinet Sonata in C, 1801

Weber:

- Turandot Overture & Incidental Music, 1809

- Piano Concerto no. 1 in C, 1810

- Abu Hassan, 1811 (C & B♭)

Works scored as C clarinet, but left to performer to choose instrument:

Auber, La Muette de Portici, 1828

Boieldieu:

- Zoraïme et Zulnar, 1798

- La Calife de Baghdad, 1800

Cherubini:

- Ifigenia in Aulide, 1788

- L’hôtellerie portugaise, 1798

- Symphony in D Major, 1815

- Mass in C minor, 1816

Hérold:

- Zampa, 1831

- Le pré aux clercs, 1833

Méhul, Joseph, 1805

Spontini:

- Fernand Cortez, 1817

- Bacchanale des Danaïdes, 1818 (composed as an addition to Salieri’s Les Danaïdes)