FINDING A USEFUL SYSTEM

When I was just about 14, I switched over from the violin to viola in my junior high school orchestra class. Part of this was to simply take on a new challenge, as we seldom learned anything above 1st or 2nd position – but mostly it was because my hand size was steadily growing at that age, and I was finding the narrow spacing of violin fingering ever more difficult to negotiate with my larger and larger fingertips. Viola was the obvious choice, and its longer reach also fit my lengthening arms quite nicely.

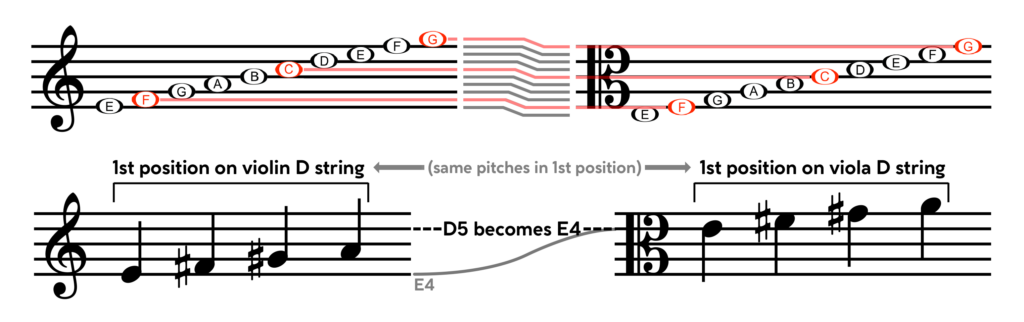

I recall my orchestra teacher describing how to read alto clef to newly-enlisted violists (usually moved over from the violins as I was): “Think of a treble staff with every line and space moved one pitch lower – then played an octave lower.” By this time, I’d been reading alto clef already for several years as a young score-reader, but I’d never actually had to play anything in alto clef. His suggestion made sense in terms of relating the fingers to positions on each string; which would be his primary concern as a conductor of very distracted younger teens who seldom if ever practiced at home. So instead of the D string’s first position starting the bottom line note of E4 in treble clef, it would now start on the fourth line of the alto clef – reading as E4 a note on the same line as D5 in treble clef.

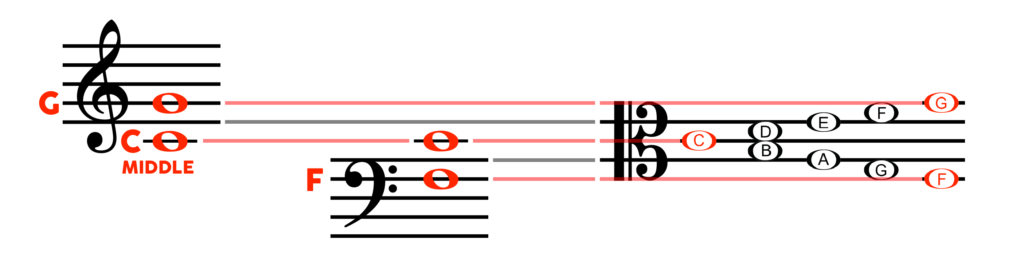

Viewed from the distance of five decades and a career of my own in orchestral music, my teacher’s advice seems like a rather baroque explanation in its practical implications. I often felt that my fellow student violists didn’t really know where they were in relationship the the violins above and the cellos/basses below. I’d taught myself alto clef reading with a much simpler system, based on my experience studying piano. The middle line was Middle C. The top line was the same G that the G-symbol of the treble clef curled around. The bottom line was the same F denoted by the F symbol of the bass clef. If I ever got lost, I could just count up or down from any of these three mileposts.

FOCUSED FLASHCARD TRAINING

Now that we have a simpler system for identifying alto clef pitches, our next concern is to improve our recognition of the note names so that reading becomes as easy as any other clef. The fastest method I’ve found is using some sort of flashcard exercise, whether as an online game or with actual cards printed up on cardstock. To be perfectly honest, while online games can be fun (and I’ve linked a pretty good one here), actual cards are better, because they allow you to focus on specific areas of training and improve them. They’re also faster, because there’s too much time wasted in an online game with moving the mouse pointer to select the right pitch. So much better to sit down with a friend or family member and run through the cards again and again until your reading skills sizzle.

Attached below are PDF files you can use to print up your own deck of cards from a home computer printer. Two files are set to pre-cut card size of metric A6 or 6”x4.” The other two files are formatted four-up to sheets of either metric A4 or US Letter – after which, you can cut the sheets on your own. Make sure to set your printers to two-sided, but be warned – some lower-cost printers cannot handle double-sided sheets smaller than A4 or US Letter. These files are for anyone to use freely without reselling, and I release them on a CCA 4.0 license.

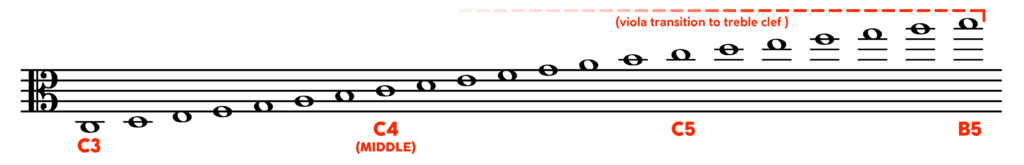

My flashcards cover nearly the full array of notes one might read in a score or part for viola, alto/contralto voice, and trombone written in alto clef (which may sometimes be a tenor trombone in older published editions). The only notes I’ve left out are those below C3, which might conceivably appear in a trombone part (more about this below). With higher ledger line notes, one should be aware that while B5 is generally accepted as the highest note for viola, the transition to treble clef may occur from lower notes depending on phrasing, readability, and continuity of finger positions (see Tip 94: Viola Treble Clef Scoring from 100 MORE Orchestration Tips). Finally, ranges of instruments and voice are indicated on the relevant cards.

Once you’ve got a deck printed out, don’t just jump in and test yourself on every card. It’s best to develop a baseline of instinctive recognition on the alto staff’s pitches first – and then add the ledger line pitches above and below. Thus, you should start by selecting out the cards from the pitches of F3 up to G4 (the F below Middle C to the G above). To help the process of memorisation and recognition develop to lightning-speed in very short order, it’s helpful to use some formulas. The formula for line notes is simplicity in itself, spelling out a word with an added letter: “FACE-G.” For space notes, one might use “Good Boys Do Fine,” though I’ve heard of some alto clef learners more hip to their music theory spelling out the notes of a G7 chord: “G-B-D-F.” Memorise these formulas, and then try them out. To really learn this quick, start as basic as possible – first testing yourself on the FACE-G line notes over and over until they’re just too easy, then the same for the Good Boys Do Fine space notes. Then mix the two groups together, and test yourself until you zip through them nearly faster than your friend can flip to the next card. Do this many times before trying out other cards, trying to get to a point where you don’t even need the formulas anymore.

The next step is to test yourself on the ledger line notes, especially the higher notes. For this, I recommend studying them separately before adding them to the first group of cards you already learned. If possible, you want your reading of these notes to be just as effortless as the basic notes of the staff. And here, there are also formulas for note recognition. For higher space notes, starting from the first space above the staff, use “ACE-G-B,” which will take you all the way up to the highest practical note for alto clef viola scoring. Higher line notes can be identified as “Boys Do Fine Always” (if only that were true), or simply the notes of a B half-diminished chord B-D-F-A.

The lower ledger lines can be remembered, adding on a couple notes we won’t bother using in the deck, as A-B-C-D-E (the A perhaps occasionally showing up in a trombone part, and maybe the B as a scordatura note tuning down the viola’s C string).

As before, test these ledger line cards to the point of extreme rapidity using the formulas, then run them together until each note is instantly recognised. Then and only then, combine all the cards together in the deck, and continue to test your skills. See how fast you can go – hopefully to the point at which you’re naming the cards faster than your assistant can flip to the next card.

At that point, proceed to Part 2 of this course: Alto Clef Scoring.

SPECIAL NOTE: Print the PDF files double-sided and borderless on heavy cardstock. The A4 and US Letter sizes will need to be quartered, so you might want to get some kind of straight paper cutter. Cut marks are provided for your convenience.