If this is your first look at my Alto Clef Reading Course, jump back to the my first two sections on Pitch Recognition and Scoring, and then read the companion chapter to this one on Score-Reading Viola. Of course, if you’re very well-versed in reading alto clef and viola parts, but you just want more information on alto trombone and contralto voice, then read on…

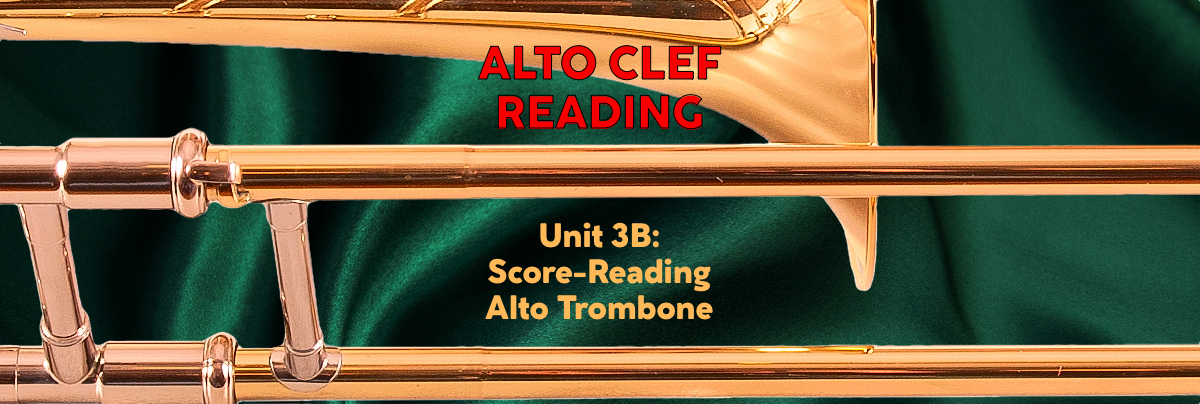

INTRODUCTION TO ALTO TROMBONE

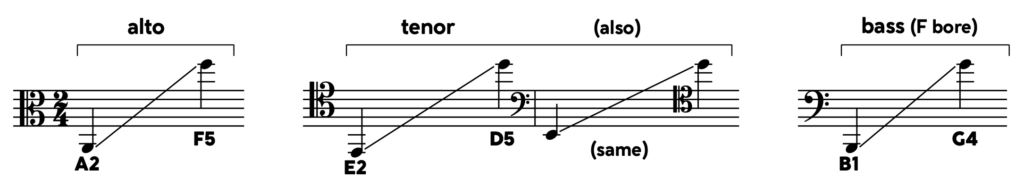

Today’s standard trombone section consists of two tenors and a bass; all of which have bores tuned to B-flat, plus triggers that open up additional tubing that help the different models in different capacities. The bass is sometimes called a “tenor-bass” for this reason, its main distinction being a heavier, wider bore and bell, and lower tuning for its trigger tubing. But back at the time of the trombone’s permanent inclusion to the orchestra, about two centuries ago, it was represented by three different models: a bass with an F bore; a tenor with a B-flat bore the same as today; and an alto with an E-flat bore. These original trombones lacked any triggers whatsoever, and pedal tones were rarely if ever scored, at least until Berlioz’s day. So the lowest standard notes started from the second partials of each instrument, fixing their ranges higher than today. Incidentally, these limitations helped to define their character in ways that fit their relevant clefs. The alto’s original range from the second ledger space note below of A2 to the third ledger line note above of F5 fits the alto clef perfectly; just as the tenor trombone’s original range from E2 to D5 fits the tenor clef, and the old-style F bass trombone’s range starting from B1 sits nicely over the span of the bass clef (though parts for it would rarely be scored all that high).

Back during this time, the early part of the 19th century, horns and trumpets were transposing natural brass instruments, only capable of playing pitches of the harmonic series (with some adjustments of tuning possible with the lip, or with hand-stopping for the horn). Cornets with pistons were available as chromatic brass; as were ophicleides; but these were rarely included as a matter of course. Piston trumpets and valve horns were still a generation or two away as stable, accepted members of the standard orchestra; so trombones represented the only dependable, common members of the brass section which were fully chromatic. Especially in this regard, the alto trombone was useful in providing essential mid-to-high range pitches out of reach for horns and trumpets. In fact, the alto trombone was so important that the main clef used for 1st and 2nd trombone in Romantic-era scores is the alto clef – the tenor 2nd part conjoined with the alto 1st part. This also shows that tenor parts were originally placed much higher compared to today’s generally lower, weightier scoring, if the alto clef could suffice to illustrate most of the range.

For more information on this unique and beautiful instrument’s history and usability, check out Chapter 49: Reviving the Alto Trombone in my book 100 MORE Orchestration Tips.

SCORE-READING ALTO TROMBONE

The eventual ascendancy of chromatic brass, especially piston trumpets, meant that the alto was no longer required. Trumpets had a purer, more brilliant sound, with more open, resonant high partials as compared to the tempered sound of the alto trombone. Alongside this development, tenor players were developing a wider range of possible pitches, going nearly as high as the alto (and today just as high). By the end of the 19th century, the trombone ensemble had evolved to two tenors and a bass, and the 2nd or 3rd trumpet took the middle-to-high role that was once the alto’s.

However, it’s precisely that tempered sound that makes the alto trombone so unique and once again desirable as an orchestral resource. It can play the high range with far less apparent strain than the tenor, even with a kind of energetic purity, or at least direct, intense clarity. The tradeoff is that its low range is far less full and convincing compared to the beefier modern tenor. But contrary to the assertions of some orchestration manuals, this lower range is far from useless.

Today’s modern alto trombones are usually fitted with triggers opening additional tubing helping to fill in the gap between the fundamentals and the 2nd partials. I have heard experienced specialists exploit this lower register with very positive effects – so long as the orchestrator accepts that this is a different sound than the tenor – a lighter, shallower range more reminiscent of the lower range of a trumpet, and yet with more colour and complexity. It would only be for this pedal tone/B-flat extension range that you’d ever need to use the bass clef for alto trombone – and I would recommend, only after having worked with an experienced trombonist with experience playing alto who can work through your ideas with you. I wouldn’t score this register in a way that placed too much dependence on the part for weight or balance – or exposed the alto’s timbre just for a fun experiment. Know exactly what you’re asking when scoring this low.

Above this pedal register, the alto trombone starts its more commonly-used pitches, with a low register starting from A2 below the alto staff up to F3 on the bottom line. Here you can see why, though I left the lowest notes out of my pack of Alto Clef Flashcards, I still diagrammed them for future reference in the Pitch Recognition post. A2 is therefore probably the lowest alto staff pitch you’ll ever read in any score, and even at that very rarely – occasionally showing up in a Romantic score as a pitch intended for the 2nd player on tenor rather than the 1st on alto. Though this low range is perfectly usable, with a confident yet mellower sound than the tenor, it was mostly avoided back during the heyday of the alto trombone. Composers of that era tended to favour a range starting from G3 or A3 of the lower middle register and up. The pitches from there to B-flat4 have a convincing, powerful sound, with that tempered quality I mentioned before; a bit of a lower ceiling to the overtones similar to viola compared to violin, or basset horn/alto clarinet compared to the standard A/B-flat clarinet. But where the viola becomes throatier in its upper register, the alto trombone starts to ring out with that intense clarity I mention above. The high register of the alto is to my mind so superior to the tenor in tone quality across the same pitches as to define it as a thoroughly separate instrument worthy of the revival that’s slowly taking hold.

SCORE STUDY MATERIALS

Combined PDF of alto trombone parts for all selections attached below

I’ve attached a combined PDF below containing all the score study examples in this post; and also edited together a video of score+audio for the same examples. This first example’s full score has not yet been added to IMSLP, nor uploaded to YouTube in a score+audio version, so what I’ve supplied is just the solo part for you to read along to. That will probably suffice, since our focus really is on alto clef score-reading for this study – but I really must stress, once again, to play through the score first on the piano, several times if you can manage it. That way the comprehension of your score-reading will be firmly entrenched. The other selections all feature full score in the video.

SCORE STUDY 2: Alto Trombone Concerto by Leopold Mozart.

This concerto illustrates many of the points I’ve made above about the alto trombone’s tone quality, and the focus of register for composers back then. In fact, this piece was written even earlier, by Leopold Mozart in the 1750’s for a colleague newly arrived in Salzburg. This may have originally been intended as a Serenade – a longer suite of pieces with soloist, as what survives is an opening slow movement in G, then two movements in D major (with a shift to D minor for the second movement’s Trio). Mozart might have planned a D major opening, and perhaps a gigue for an ending with a fast 6/8.

Mozart focuses mostly on the upper middle register in scoring, and carefully sets up notes in the high register for maximum coloristic impact. You can hear the warm, complex yet powerful quality of the middle register – a true alto instrument if there ever was one. Then we hear those beautifully direct upper pitches; going no higher than C5 and D5, but with such ringing elegance that they stick in the ear long after the moment has passed.

Additional Alto Trombone Score Study:

(Instrument parts included in attachment, score+audio in video link above)

Wagenseil Alto Trombone Concerto

Beethoven Symphony no. 5, Mvt. IV, bars 1-87 (2nd repeat)

Brahms Symphony no. 3, Mvt. IV, bars 149-172

Brahms Symphony no. 4, Mvt. IV, bars 113-137

There are a few other alto trombone concertos, some of which are transcriptions of other pieces. The Wagenseil concerto is one of those scored for alto trombone from the beginning. In some ways, Wagenseil is even more conservative than Mozart – keeping the instrument’s range between A3 and B-flat 4 (with a couple C5 notes here and there – and scoring in the home key of E-flat. Nevertheless, the Mozart is probably easier to play, as Wagenseil is a bit more adventuresome with his harmonic changes and freedom of melodic motion.

In addition, I’ve linked a few additional works in IMSLP/YouTube score + audio for your study – in this case, symphonic excerpts from Beethoven and Brahms including alto trombone in a section with tenor and bass. As mentioned above, in some cases the tenor trombone will team up with the alto on the alto staff. Watch for how the three trombones work together as a low-to-midrange choir within the orchestra: often supporting the harmony in a tutti passage; and occasionally blazing out in octaves, or doubling the melody from below.

Click here to jump to the final Unit 3 study on Contralto Voice – then try Unit 4’s sight-singing and melodic dictation exercises to finish the course.