If you’re new to reading the alto clef, but you’ve taken the time to drill yourself on Pitch Recognition and Scoring, especially after studying the posts I linked in this sentence, then you’re ready to take on some practical information. Which instruments use alto clef, and how does the alto staff relate to their ranges and registers? I’ll answer those questions below, and supply some links and suggestions for score-reading study. My ultimate goal with the training in this series of posts is to build your familiarity with alto clef to the point at which reading and understanding its notes will be just as easy as those in treble and bass clefs.

Ex. 1: Alto clef instruments of viola (most common), alto trombone, and contralto voice (in the image above, the great Maureen Forrester). The latter two are in some ways historical in their appearance in a score, at least in alto clef; but their parts in older editions should be easily read and understood by today’s conductors and composers.

GROUND RULES

Instruments. The alto clef instruments in question are viola, alto trombone, and contralto (alto) voice; but before we examine each in detail, let’s lay down some general ground rules that apply to all three (with a couple little exceptions),

Concert Pitch Always. The first thing to remember is that alto clef never transposes. The notes of the alto staff are always in concert pitch. This is because reading systems for transposing instruments are almost always based on fingering positions that use the treble staff as a reference chart. Alto staff instruments, on the other hand, align with reading systems based on concert pitch that reference other concert pitch instruments from each individual family or group – strings, trombones, or voice. Since none of these groups of instruments transpose (except trombone in some band scoring) – and their scoring is often highly integrated within their families in harmonic and melodic scoring – it’s only natural that the alto clef stay firmly in the bounds of the concert pitch system.

Usually, Only Viola Changes Clef. Further, in the case of scoring parts, there will be no need to change clefs for any of these instruments – with the exception of the viola, which has an extended altissimo range reaching up into the ledger lines above the treble staff. (Alto trombone may also change to bass clef in the very rare case of pedal tones and lower trigger position scoring.) Even so, most viola scoring fits comfortably within the bounds of the alto clef; while scoring very far outside the central range of alto staff notes from C3-E5 would be exceptional for contralto voice or alto trombone. But as we’ll see in the next post, alto trombone parts are sometimes scored in tenor clef; while the trend of scoring contralto parts in treble clef dates from the middle of the 19th century.

Characteristics Vary. Nevertheless, as we’ll see in the following thumbnail examinations and comparisons, tone quality and technical capability vary between instruments. While all certainly possess a rich, sonorous low register, each instrument’s mechanics and timbral shifts result in a variety of different characteristics in their middle and high registers.

Alto Clef Instruments As Extensions of “Standard” Models (but not the only alto range instruments available). One last observation is that the alto identity of an instrument is in some ways an extension up or down from what might be considered the standard model; downwards from violin and soprano voice in the case of the viola and the contralto voice; and upward from the tenor trombone for the alto trombone. Of course, these three examples aren’t by any means the only alto representatives in concert music. Alto saxophone, alto (aka tenor) horn, alto clarinet, alto flute, and even some instruments that lack the “alto” title but share the range such as English horn; all might well play alto register parts with some effectiveness. But since their reading systems are linked to the association of fingering positions on a transposing treble staff, they don’t use alto clef.

Ex. 2: The above ground rules illustrated across an alto staff.

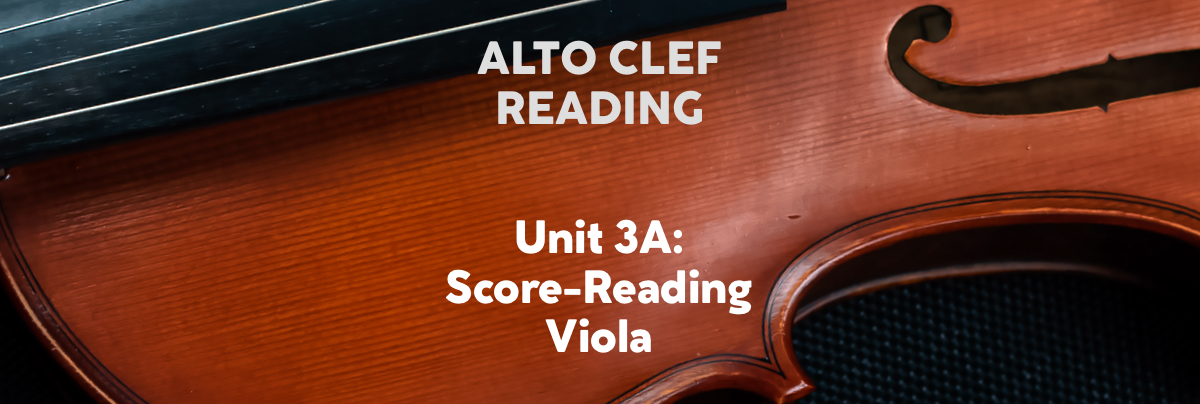

SCORE-READING VIOLA

Viola is without a doubt the most ubiquitous of all alto clef instruments, in pretty much every work that features a full string section, not to mention string quartets, unaccompanied pieces, and other chamber music. Its open strings lie neatly across the span of the alto staff; from the low C under the first ledger line below, up to the high A string sitting over the top line of the staff above. The A string is distinguished from all other open strings of the standard string instrument family in that every note written for it is outside the range of the home staff. The result is that violists are used to reading ledger lines above the staff with greater alacrity than composers may suspect – though of course it’s unwise to push their reading higher than B5 before shifting over to treble clef.

Within the given alto staff range of 3 octaves from low C3 to high B5, the section violist’s technical capacity should easily equal that of players on any other string instrument. A high B5 under the 4th finger (the pinkie finger, for those readers unfamiliar with string instrument finger numbering) means that the violist is in 5th position on the fingerboard. Higher than this, the wide shoulders of the instrument represent an obstruction to the wrist, forcing the left hand to arch ever more unnaturally around and over the instrument. While the altissimo range is by no means impossible for the viola, a degree of casual virtuosity on such high notes may be limited to professional soloists and front-rank section players.

I’ve covered some of this information in other courses and orchestration tips – let’s review the most relevant points in the context of your study of alto clef. In the chart below, the pitches of the viola’s open string are indicated by Roman numerals: IV = C3, III = G3, II = D4, and I = A4. The weight of individual strings gives each register a distinct characteristic (though a good player will play smoothly from register to register). The C string’s heavier weight results in a rich, soulful sound in cantabile playing; and fierce, gruff articulation in accents and loud, abrupt playing. Some melodic passages may push this quality up into the middle register by staying on the C string for an octave or more of range. Then the G and D strings are progressively lighter in thickness, with less natural projection and a calmer character. Nevertheless, the middle register of the viola is not to be underestimated in its expressive capabilities. It’s here where the compromises of reduced string length and sounding board capacity result in a strikingly heartfelt, emotionally generous quality; which only grows greater in throaty yearning as the music rises up to the first-string A. Ignore the clichéd, downplaying descriptions of this register as “nasal”. Here is one of the greatest resources for expressing an ineffable sense of longing, or a quality of wonder at new worlds coming into being. The cushioned brightness of the high register is unique, with much new ground to explore for orchestrators and composers of imagination and depth of feeling. The altissimo register can be eerily unsettling, or beautifully endearing, almost like miniature cello in its elevated expressiveness.

Ex. 3: Viola range and registers. Though this information may be familiar to you by now through study of orchestration manuals, or exposure to some of my resources, treat this example as a way to absorb the viola’s range across the alto staff, and how each register inhabits a different part of the staff’s layout. Notice particularly how the lowest string/low range sits across the low C up to the first space note of G; and then how the middle register stretches upward from there across the entire staff up to A above the top line. This middle span of notes is of utmost importance in all manner of scoring, and justifies the use of alto clef as the foundational means of orientation for the instrument. Then climbing above the staff we encounter the high range, which is very commonly exploited for its usability and strength of support below the 1st and 2nd violins (and occasionally for its unique qualities as a featured voice). The altissimo register, which is far rarer, should only be used with very specific thematic and textural goals in mind.

SCORE STUDY 1: Bach Brandenburg Concerto no. 6 for two violas.

IMSLP Post with Downloadable Score & Parts

Video with Score + Audio

The purpose of this post’s score study is to continue to build familiarity with the pitches designated by the alto clef, as well as a deeper understanding of each instrument’s scoring across this landscape. You want to be able to look at an alto clef part in a score, and immediately understand not only the identity of each note, but its register and quality of tone, not to mention its purpose within the greater scheme of the music (especially as alto register instruments tend to have internal parts that are only occasionally thematic or play the bass line.

Each featured score for study is linked to a score + audio video for your convenience. But before you watch each video, you should click through to the IMSLP link and open the instrument part. Prop your laptop or pad on top of a piano (or print out the part), and play through large portions of the music, reading off the alto clef part as you play. This will backstop your comprehension of the written score, absolutely ensuring that every note is understood. Then and only then should you apply yourself to reading the score along to the music.

Our first selection, Bach’s 6th Brandenburg Concerto, offers an embarrassment of riches, with not one but two solo viola parts, both of which stay firmly within the bounds of the alto clef. Since the scoring is highly imitative, one part frequently echoing the other, it’s not necessary to play through both parts simultaneously in the context of this exercise. Play through several passages of the first and third movements in the first viola part, and trade off between the second and first viola part in the middle movement.

Bach composed the concerto in the key of B-flat; which at first might seem like an unlikely key for a duo viola concerto; until one notices certain advantages built into the range and registers of the instrument itself. The dominant pitch of C in the V chord of F major is often employed by Bach on the low open C string, as the line dips down to rise up again on its way to a V-I resolution back to the home key of B-flat. There’s also a natural general range of pitches that fit right into the alto clef and the viola’s middle register, from the bottom-line F3 up to the first ledger line of B-flat. Most of these pitches will be played in first position on the gentler middle two strings of the viola, lending the main body of the concerto an earthy, glowing sound picture. Higher up, Bach treats the pitch of G5 as the upper limit, with some occasional colourful scoring above the staff – sprightly in the outer movements, yearning and soulful in the inner movement.

This piece is sometimes looked upon by violists as a fun piece to play through with each other in a casual way, as much of it is not too hard in terms of individual phrases. The whole concerto as an ensemble piece is actually quite difficult, though, especially in pulling off some of the shifts of register and finger positions in a way that sounds effortless.

Ex. 4: J.S. Bach, Brandenburg Concerto no. 6, Movt. I, 1st viola solo part bars 1-21. Some of the above points illustrated.

From here, continue with the next two Score Study exercises in this post before circling back to take on more viola score-reading. As with the Bach, click through to the IMSLP page first and play through sections of the solo part on piano; then open the video and score-read along to the audio.

Additional Viola Score Study

Berlioz, Harold in Italy

Video with Score + Audio

Brahms, Sonata no. 1, op. 120 for Viola (or Clarinet)

Video w/Score + Audio

Clarke, Viola Sonata

Video w/Score + Audio

Hindemith, Sonata for Unaccompanied Viola op. 25, no. 1

Video w/Score + Audio

This turned into an enormous post – best to catch our breaths before moving onto the next post, finishing off our study of these instruments with:

Alto Clef Reading, Part 3B: Score-Reading Alto Trombone

Alto Clef Reading, Part 3C: Score-Reading Contralto Voice