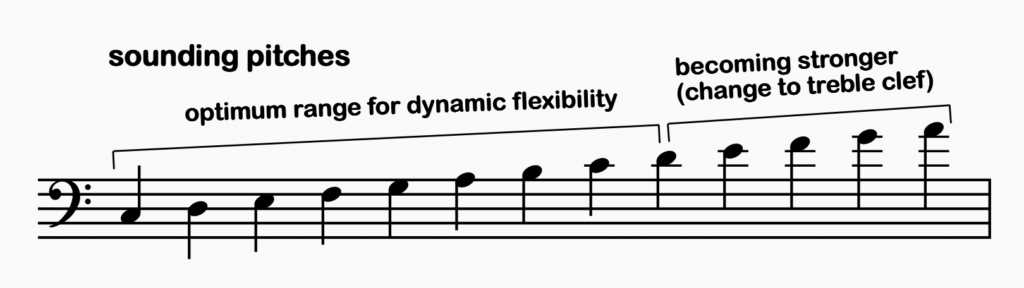

For better control in delicate scoring, use the horn’s middle register, especially in the octave between written G3 to G4 (sounding C3-C4). For this specific area of range, bass clef is recommended if the orchestrator is scoring in concert pitch.

I recently moderated a composers workshop hosted by the Academy of Scoring Arts, in which a pocket orchestra had been hired to read ten 1-minute scores. The instrumentation consisted of flute, clarinet, horn, harp, and string quartet plus double bass – nine players in all. Every score was fascinating and delightful in character, and it was an honour to be asked to contribute my advice and perspectives to the event.

If there was any common problem of approach amongst most of the scores, it had mostly to do with the horn scored out of balance. Smooth, elegant textures were pushed out of shape by the horn’s strident tone – while more lively passages would become dominated by the horn’s sense of urgency. I talked the composers through different options for balancing their scores – but in most cases, simply dropping the horn an octave not only corrected the imbalance, but also added a wonderful sense of warmth to the winds and strings above in harmonic or melodic roles.

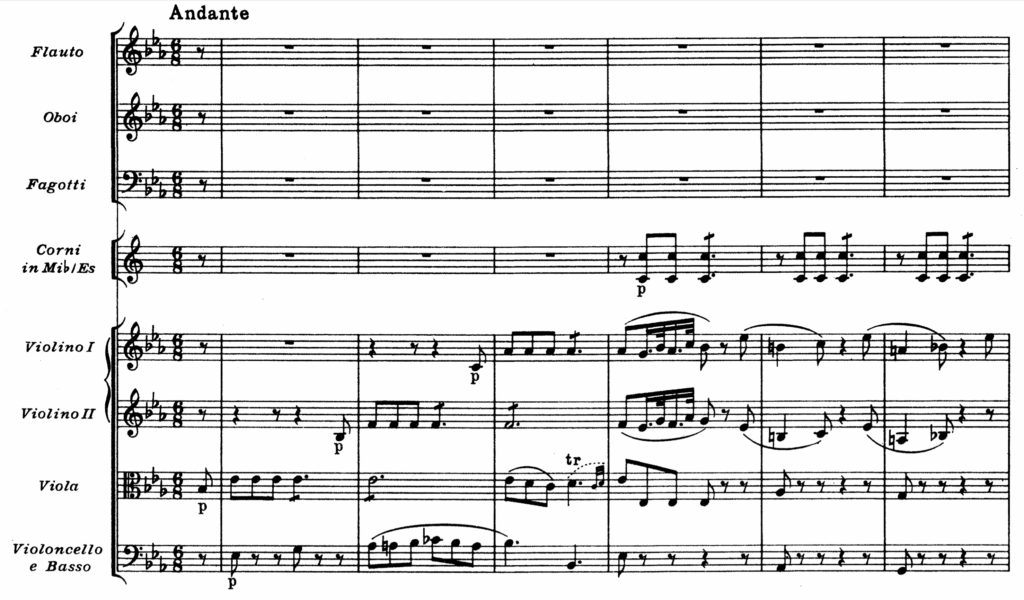

The chief culprit in this regard? Scoring in C, causing the composers to impose a higher general tessitura onto the horn. The range of most parts sat well within a concert-pitch treble staff, trending to the middle. For the horn, that is a stronger part of its range, with written notes at the top of the staff; only a few steps away from its written high C. Small wonder that the hornist at our event was barely able to tone down their playing, especially in a chamber context with lighter textures and limited tone-weight from the other players.

Many horn players will tell you that the force and projection of their playing drops considerably each octave lower in range. But this weakness becomes a strength when applied to subtler textures and interactions. Even just dropping down to the lower part of its middle register, the horn can play with extreme softness and delicacy, blending imperceptibly into a glowing sound picture, or merging seamlessly into softly pulsing winds or strings.

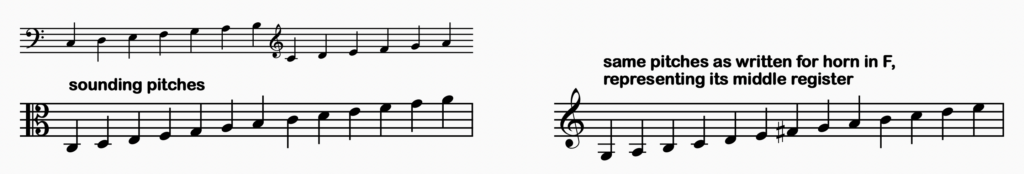

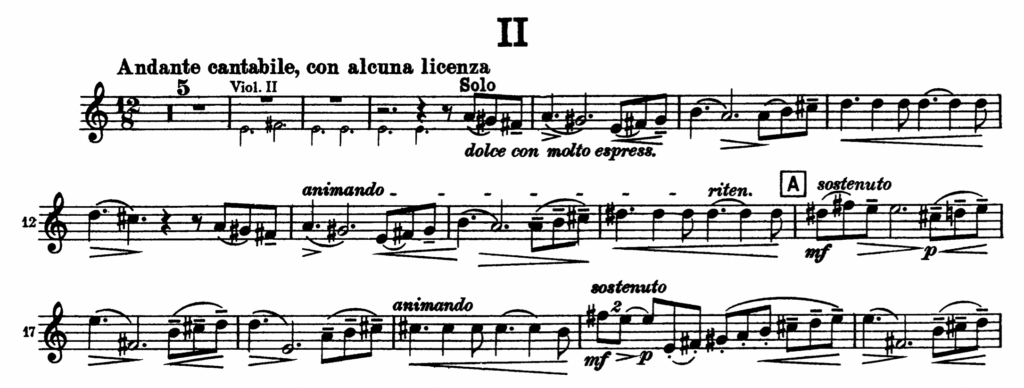

But where does this leave our composers scoring in concert pitch? Well, consider that the concert horn has sometimes been compared to the viola for its role providing a middle voice; filling in a harmony, tracking a melody from below, providing some inner strength in a texture, and generally bulking things up from time to time. Considering the viola’s basic range in that capacity, from its low C string up to its A string, that translates very well to the middle register of the horn: from written G3 up to E4.

This is the sweet spot for a lot of horn scoring – and certainly its most flexible dynamic range. A player can produce the most noble of calm solo lines – or belt out a gutsy, heroic blast without any strain. In a situation with very light scoring, especially in a chamber ensemble or Classical-era orchestra, the horn can reduce its intensity considerably to match softer textures, or harmonise with winds from below in ways that avoid dominating them. Particularly in the first octave, from written G3-G4, the horn can play with a very soft, accommodating tone.

But I’m not suggesting that concert pitch composers actually use an alto clef for scoring horns in this range. That’s just adding another level of complexity, especially for beginning orchestrators. Rather, I recommend using bass clef for this range. That puts the focus of visual convenience right onto the sounding range of most usability in delicate scoring: C3-C4 (G3-G4 as mentioned above). The more control and subtlety the horn part requires, the fewer ledger lines upward the orchestrator should employ.

This turns the horn into a kind of tenor-range instrument – at least in chamber scoring. But of course, that position fits well within the wind quintet between the bass duties of the bassoon and the alto character of the clarinet (speaking in typical scoring ranges); and also in pocket orchestra scoring, where that register often needs more support. Bass clef scoring of horns is certainly a common enough approach in concert pitch scores for film and some contemporary music – so it’s probably a good default for a composer building their chops as an arranger and orchestrator. Just make absolutely certain that your instrument parts are transposed to F, and in treble clef for pitches above written E3!* All too many orchestral readings have gone astray from players receiving parts written in bass clef with ledger lines reaching high above the staff. Never submit a horn part with high ledger lines above the bass staff!

As to the participants whose scores I evaluated recently, many of their horn parts ranged in the upper middle register and even a bit higher in places. While this is a terrifically expressive part of the horn, it’s more outspoken and resonant, with the tendency to blot out winds above it in harmonies – at least on a one-to-one basis as occurred in those scores. It absolutely has its place, though, when you really want a solo to be heard, especially with a compelling sentiment or a bravura fanfare. As these notes go up into the next octave of range, here’s where you’d want to change over to treble clef in your concert pitch scoring, rather than using bass clef.

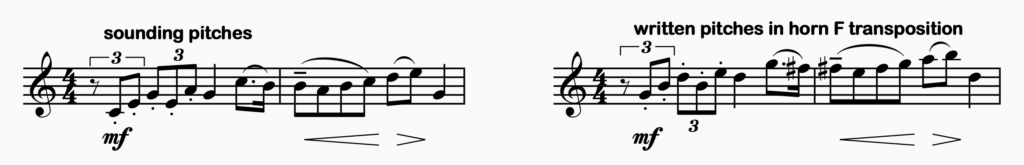

Of course, all of the above in reverse is one of the strongest arguments for the concert pitch orchestrator’s eventual changeover to reading and scoring in transposed pitches (at least in concert scores if not film). Seeing what the player sees in their part instantly reveals the effectiveness of the scoring – both in the individual technique and capabilities of the player, and in relation to the full score’s other parts, whether transposing or normally written in C. Even if a composer’s main focus is firmly on film scoring, the ability to read and transpose horn parts at sight opens up a whole world of meaning in existing concert scores of the past three centuries. Don’t let that awesome library stay in the closed stacks of your comprehension. Let F transposition reading become as familiar as your ABCs.

*with some exceptions. If a part is generally in the horn’s low register, notes on the bass staff may reach higher within an overall phrase that’s centred lower in pitch.