While dovetailing a line between woodwind instruments can feel very natural, truly seamless doubling requires the use of compatible registers between members of the same family.

Sometimes, a composer conceives an exposed line that’s so wide in scope that it requires dovetailing between instruments – and yet there may be a need to keep that changeover as seamless as possible. With strings, this is a fairly simple proposition, as most registers are nicely balanced to one another, and it’s easy to move from basses to cellos, cellos to violas, or violas to violins, without too great a disparity in timbre. It’s not so easy in winds, where the different families have a wide variety of contrasting timbres and registers – and even two wind instruments of the same family may have only limited ranges in which truly seamless dovetailing can occur.

I’ll cover the problem of dovetailing between winds of different families in the next tip – in the book, this will be the next chapter – but let’s focus on the second problem first: optimal registers for seamless dovetailing between instruments of the same family. And by seamless, I mean a hand-over between the two players sounds like the whole line is being played by a single instrument.

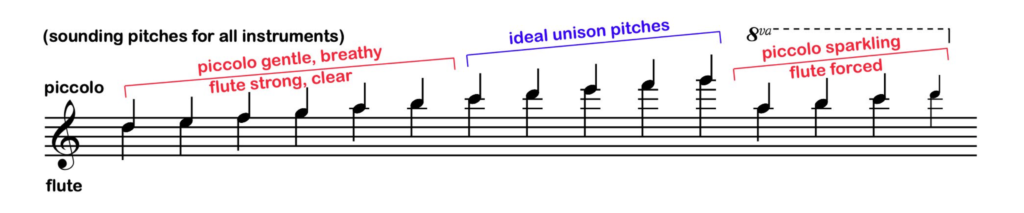

In 100 MORE Orchestration Tips, Chapter 14, I discuss the problem of Piccolo-to-Flute Unisons – how the middle register of the piccolo and the middle of the flute’s high register share the most compatible balance. Lower than sounding C6, the flute starts to dominate the further down the range goes. Above G6, the piccolo comes into its own with a lot of power and assurance, while the flute gradually gains a more stressed, forced character up to its top D7.

Just as those middle pitches are ideal for unison doubling, they’re also perfect for seamless dovetailing. Supposing that a line started lower on the standard flute, rose through its registers, ultimately finishing a note or two too high in its range. Dovetailing over to piccolo will be the only way to achieve the full range of notes – and this will also give the line better dynamic control across its entire scope, especially in allowing for a gentler ending on higher pitches.

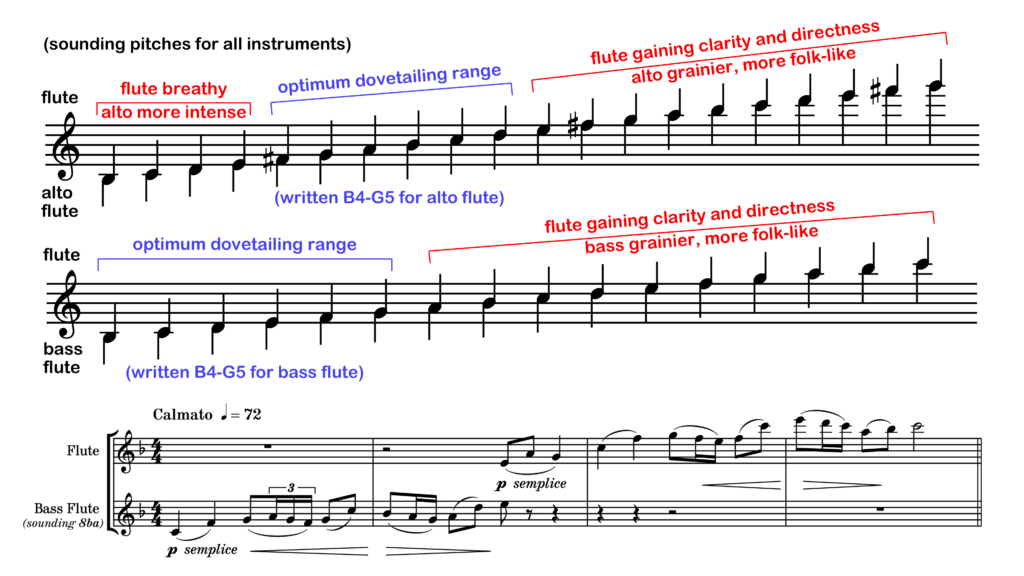

A perfect hand-over point is not quite so cut-and-dried between the lower flutes and the standard flute. Part of this has to do with the natural tendencies of alto and bass flute scoring to focus on the lower register. Both instruments will have an exaggerated breathy quality in their low registers, and then gain a cooler, grainier, folk-flute sound above written C5. These higher registers are so different in character from standard flute over the same notes at pitch, that seamless dovetailing is usually not an option. And yet I’ve scored very direct, forceful upper-register alto flute lines that aren’t too different in character from middle-register standard flute. If I were forced to figure out a near-seamless dovetailing between the two instruments in these registers, I might be able to make it work. But I’d still have concerns. And dovetailing from upper-register bass flute to middle register standard flute would probably be even more problematic. So I’d probably recommend a more dependable hand-over point from written B4-G5 of both instruments to the standard flute. That way, the velvety quality of all the instruments provides a bridge which helps to cover up any pronounced differences.

Below, the same sketch as Ex. 2, reimagined an octave lower for bass flute to standard flute. Notice that the dovetailing occurs in the 2nd bar now.

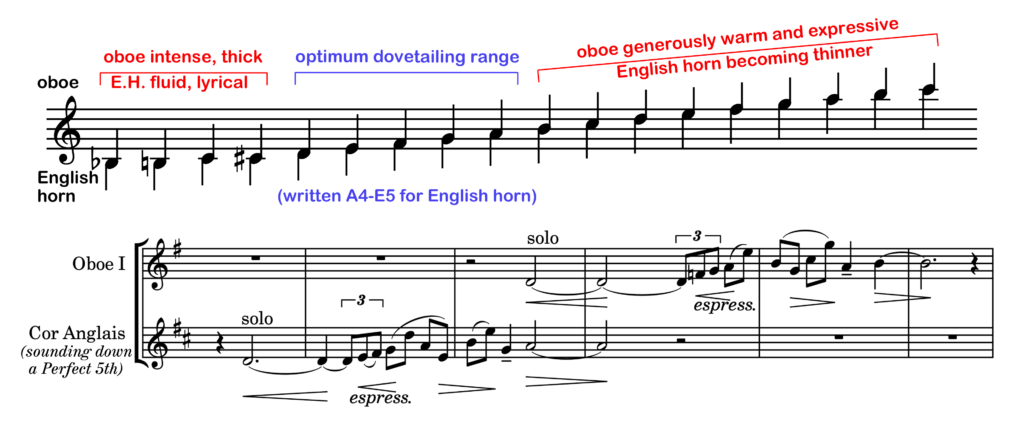

Comparing the quality of timbre between oboe and English horn, one might assume that any lower pitch might sound similar enough to switch imperceptibly between instruments. But that’s not quite right: the very lowest notes of the oboe can have a quite pronounced character, and lack the subtlety and range of control that the English horn possesses on the same sounding pitches. And then in reverse, as the English horn starts to rise above the treble staff, its peculiar thinness is quite unlike the oboe’s generous warmth and command of expression on parallel pitches. So the optimum register for seamless dovetailing rests between the sounding pitches of D4 to A4 – perhaps even going up to C4. As you can see in the example below, these are the written pitches of A4 to E5 on English horn – with the possible extension upwards as high as G5. I’d avoid dovetailing on these higher pitches in subtler, very exposed scoring – but for a line that bubbles merrily along, or soars with more power, sounding C4 is probably fine.

Below, Goss, Tane & the Kiwi, bars 110-115, dovetailing English horn-to-oboe solo. Notice the handover note of sounding D4 from bar 112, with fadeout/fade-in dynamics.

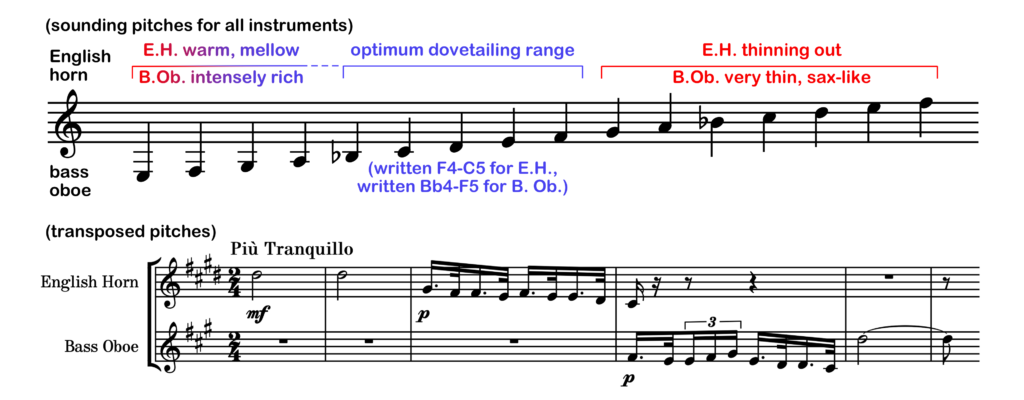

I’m not going to delve too deeply into the topic of dovetailing between bass oboe family instruments to English horn or oboe in this tip – as there are different qualities of timbre between the Lorée-style baritone oboe, the Heckelphone, and the lupophone that might have a variety of outcomes. But should the issue ever arise for the lucky orchestrator, perhaps in a film cue, I’d probably recommend the sounding pitches of B-flat3—F4 above as a transitional range between bass oboe and English horn. One might extend this range downward all the way to sounding F3 if the hand-over point is at a softer dynamic, at which the bass oboe’s intensity of timbre won’t overwhelm the English horn so much. And I might avoid attempting any kind of seamless dovetailing between bass oboe and standard oboe, as the timbres of their registers really diverge considerably on any sounding pitch. That doesn’t mean I’d never dovetail between the two instruments; just that I wouldn’t expect such a transition to be truly seamless.

Below: Delius, A Dance Rhapsody No. 1, bars 1-6 of Reh. 5. To dovetail between these two oboe family instruments, Delius chooses the pitch of written C in English horn/written F4 in bass oboe (sounding F3). Notice that the dynamic is a simple p, which has a more balanced sound between the two.

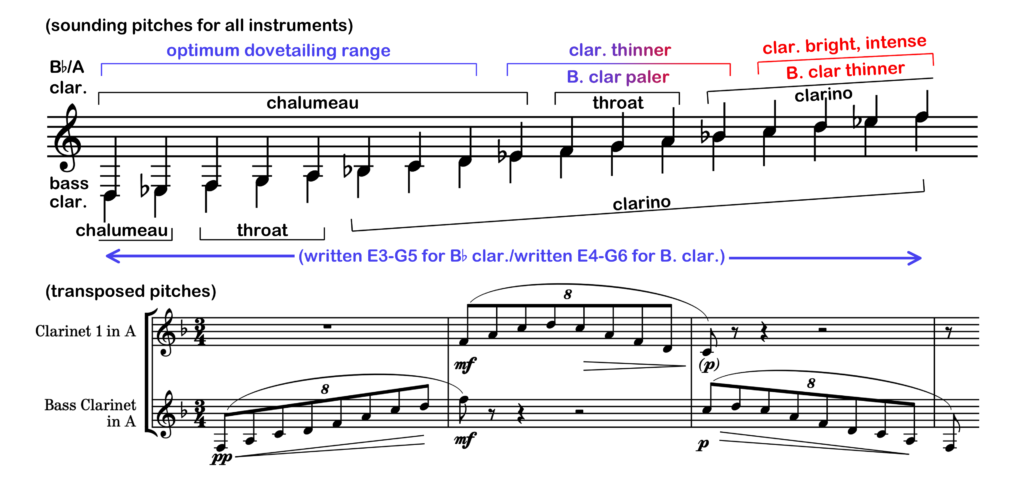

The wonderful evenness of tone and dynamic strength across all registers of both the standard B-flat/A clarinet and the bass clarinet provides a much wider variety of opportunities for seamless transitions. It just depends on what kind of sound, and what dynamic. Softly played, nearly the entire common range of shared notes is generally compatible. There’s a beautiful sweet spot where the chalumeau registers of both instruments meet up at the bottom in equally rich and sonorous tones. From there, the bass clarinet’s wider bore and more generous timbre make its throat tones and lower clarino notes a very workable area of transition across the rest of the standard clarinet’s chalumeau register. Then going up a bit further, the standard clarinet’s throat tones and the bass clarinet’s lower clarino register are very compatible. The thinner quality of the former matches up beautifully to the paler quality of the latter, so long as the dynamic isn’t much stronger than mf. But pushed to its highest, the bass clarinet’s clarino register becomes less immediately subtle and free than the same sounding notes on standard clarinet – though a world-class bass clarinet player can accomplish almost anything up there.

Below, Ravel, La Valse, bars 7-10 of Reh. 10. The bass clarinet swoops up to transition from its middle clarino register written F5 to the 1st clarinet’s top chalumeau note of F4 (sounding D4). Notice that the dynamic is mf. After arcing over the arpeggio in the second bar, the 1st clarinet transitions back from a written chalumeau Middle C to the bass clarinet’s lower clarino C5 (sounding A3). I have left the original example as composed and scored by Ravel – though today’s clarinetist would play the bass clarinet part on an instrument tuned to B-flat rather than A.

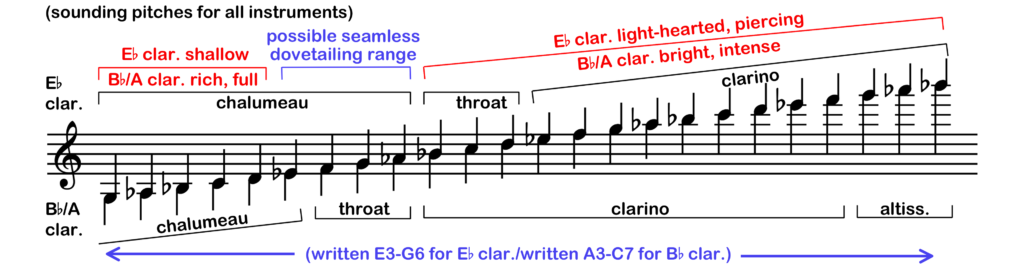

Transitioning from B-flat/A clarinet to E-flat clarinet isn’t such a breeze. Absent the consistent richness of tone of its lower-pitched sisters, the E-flat has a tendency to stand more alone. Its chalumeau register has a shallowness that doesn’t really translate compatible to the standard clarinet – and likewise, its piping clarino register is far more light-hearted, or piercing, over available parallel pitches. Perhaps the best bet for dovetailing would be between the standard clarinet’s already thinner throat tones (plus a couple semitones on either side) and the E-flat clarinet’s upper chalumeau register. But it’s still a shift that might sound obvious no matter how carefully it’s scored.

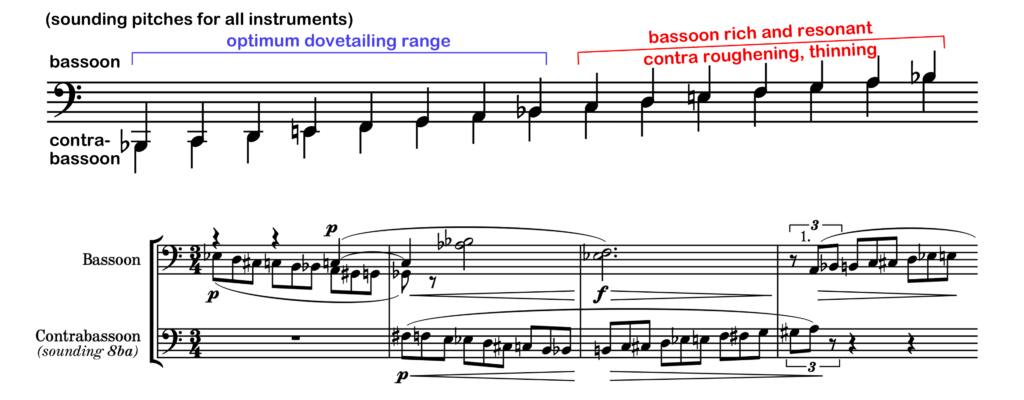

That simply leaves dovetailing between bassoon and contrabassoon – and as these are instruments that are intended to work fairly well together in most situations, there’s a lot of seamless transitioning between the two as a matter of course in orchestral bass line scoring. The lowest octave of the bassoon dovetails very well across the same sounding pitches of the contra’s second octave – though for very exposed soloing, one might want to avoid dovetailing on the bassoon’s lowest two semitones, B-flat1 and B1. Higher than sounding B-flat2, the pitches start to push up into the contra’s rougher, thinner tenor register, where the quality of tone parts ways most decidedly with the bassoon’s richer upper bass register.

Below, Ravel, La Valse, bars 2-5 of Reh. 40. The dovetailing between bassoons and contra will be completely seamless. Notice that Ravel puts the second transitional point on the middle note of a triplet – a trickier spot at that tempo than the previous dovetailing two bars before, but still doable.

Of course, any of the instruments above might dovetail over any notes of shared range, seamless or not, and still produce a remarkable effect. This tip isn’t condemning all less-than-optimal transitions – nor should the reader avoid such dovetailing in every case out of principal. But if the orchestrator really wants to transition between two woodwind instruments of the same family in ways that are virtually imperceptible to the listener, then the above information might prove useful.