Morricone’s task in scoring The Hateful Eight was both enviable and unenviable. Director Quentin Tarantino gave him a completely free hand with the script, allowing him to score whatever he liked according to what his muse spoke to him. This gesture of trust and respect is not unlike that afforded to John Williams by more firmly established mainstream directors like Spielberg and Lucas – the knowledge that the composer’s instincts can be counted on every time. On the other hand, what was Morricone scoring in this case but an extended parlour-room drama? It was curiously static, especially considering Tarantino’s penchant for movies where people go places and do things along the way. In this case, aside from an introductory section in which characters travel to the main setting, a flashback, and a couple of excursions to the outhouse and the stables, the entire action of the film occurs in the large central room of a roadside lodge. That’s a challenge for a composer. The music can easily get too large to fit the room – or dither in cautious mundanities. To make things even more difficult, this is a very talky picture – even for a Tarantino film. People taunt each other, yell at each other, and even shoot each other, but they don’t really go and do things that require motion from the camera or the music. It’s all down to the intensity of the actors, and so the music must adorn one emotional moment after another without exhausting the audience.

I felt that Morricone has really lived up to the task with something extraordinary. Aside from the obligatory bits of anachronistic pop music injected into the scenes by Tarantino and his music supervisor, which added very little to the mood of the film, the soundtrack was excellent. The orchestration was particularly effective. Once again, as with Sicario, Carol, and Star Wars: The Force Awakens, the orchestration was essentially done by the composer – a promising trend when the level is as high as it’s been across the board.

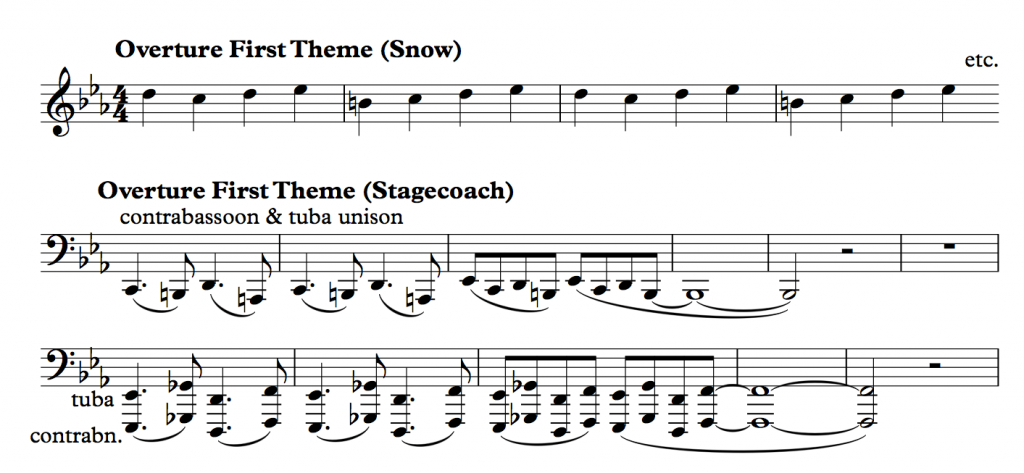

Nevertheless, the strongest scoring was as you’d expect – those scenes which depicted action and landscape. Accompanying standout cinematography of an oncoming blizzard, the Overture opens the film with icy menace. In fact, Morricone realises as much as anyone that the most dangerous antagonist in the picture is the relentless, unforgiving snow, whose lack of warmth seeps through to the almost complete amorality of the characters. Here he paints the whiteness with very full but muted strings playing long tones and punctuating tenuto-staccato chords, while the fluttering of the snowflakes finds expression in slow tremolo lines by English horn. The top pitches of these chords are turned into the persistent winter theme of film by legato violins and violas. A combination bass drum/tam-tam hit introduces an introspective vibraphone solo, which reiterates the winter theme in broken octaves. Under this, the second theme emerges, a classic “bad hombres” theme worthy of Morricone’s best work in the Spaghetti Western field (later revealed to be the stagecoach theme). This is played by contrabassoon and tuba, first in unison, and then in octaves as the theme rises in pitch, the contrabassoon grinding down below.

Descending minor chords follow in radiantly-textured winds and strings, into which a high horn solo is injected, reaching all the way up to a written Bb above the staff. Listen to how this lights up the texture to a glow. After a reiteration of the winter theme, the music tails out softly with little thematic touches by the old standby of tripled alto flutes. It’s really a reminder of how rooted in the 1960’s-70’s this music is, and how Morricone has built on some of these classic textures and sounds into a personal style that’s accompanied many genres of film (as has John Williams’s style).

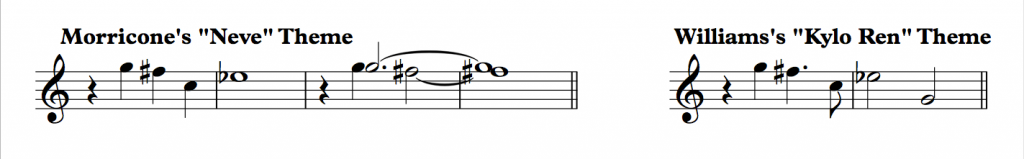

The soundtrack release is a bit of a jumble, with the tracks in order of what was probably felt to be the most impactful as a listening experienced – compared to most other soundtrack albums that list the tracks more or less in the order that they appear in the film. For instance, though the Overture cue and parts of the Neve (Snow) cue occur first in the film, they appear 2nd and 8th in track order. Neve is more iciness, with a theme emerging over a massively-spread open C5 interval that’s eerily similar to the Kylo Ren Theme of Star Wars: The Force Awakens, though certainly this is just one of those coincidences that occur when thousands of composers are working on hours of music every year.

The scoring of this theme is very cool, very period to the 1960’s. It’s a triple octave of upper strings, doubled by clarinet and vibes. The top line of strings is played with artificial harmonics doubled by very soft piccolo, right at the resonance point for the clarinet’s overtones. The end of the first episode end on a long minor second of F# and G, and its great to hear the conflicts this sets up. As the passage continues on, a solo clarinet in chalumeau register muses on the second theme, as if pondering the helplessness of the situation, and the oncoming bloodbath to come.

Of course, the track that’s gotten the most attention, at least to judge by YouTube views and Facebook discussion, is the 7th one in the soundtrack release: “L’Ultima Diligenza di Red Rock” (The Last Stagecoach to Red Rock), No. 2. It’s a great pastiche of classic Morricone scoring techniques. The opening drumkit-style pattern played on timpani seems to frame the “bad hombres” theme, but it’s a false start: the real action kicks in, heavy on lower brass and double-reeds with little psychotic strings reactions that unfold into full-flown countermelody as lower heavy brass dig into the theme with a will. I like the climactic passage from around 1:20, with violins sweeping up to high C, under which muted trumpets blast angrily away against aggressively rising lower strings. It’s great how Morricone returns to the initial scoring, and then brings all the elements together with huge passion and emphasis by the end.

There are many other great moments in the score, but here are my two favourites. First, the cue “Raggi di Sole Sulla Montagna” (Rays of Sun on the Mountain), with its expressionistic winds rambling in and out of chilly but radiant string harmonies. This is first-class concert music scoring that could easily stand on its own on a symphony orchestra program, and bespeaks the composer’s origins as a 20th century composer who learned his craft when music was heading into arcane regions. Here, those directions are transformed from self-referentially indulgent to pictorially virtuosic.

The other cue at the top of my list is “La Lettera di Lincoln” (The Letter of Lincoln), which starts with a simple duo between trombone and ringing solo trumpet, so clear and effortlessly effective that it immediately reminds one of the fact that Morricone was also at one time a profession trumpet player. He knows every trick and every nuance, every good note and ever strength of register. This is some of the best trumpet solo scoring in film, right here, and it should be textbook for composers to study and emulate in their own work.

I’ve included links below to a couple of extra goodies floating around on YouTube: a reel of moments taken from scoring in the Czech Republic and at Abbey Road, and an interview with Morricone (the translation to which is in the information of the video). I hope that you’ll really give this expertly scored soundtrack a good listen, and learn what you can from it. I found it enormously revealing and helpful to my understanding of cinematic scoring style, full of many tricks and cool ideas that could stimulate my own creativity. But is that innovation and classic mastery Oscar-winning? My thoughts about that will be coming soon for this score and all the others, after I have a look at Bridge of Spies tomorrow.