(Tip no. 30 from 100 MORE Orchestration Tips)

The use of an A extension may give you an extra half-step lower in a bassoon part, but it’s not without consequence.

The lower limits of any orchestral instrument are constantly being challenged. Double basses have had their low E strings turned into extensions down to low C, or added to with an individual C string that may even be tuned to low B when the music requires it. Trombones have had the gap between their low E and fundamental B-flat filled in by the use of the F trigger. Clarinet low ranges have been extended from nearly the very start with basset models, the principles of which have now been applied to the bass clarinet to give it a low written C/concert Bb1. Even very standard winds have evolved over the centuries to possess an extra half-step of low range, like the now-ubiquitous B foot for flutists and low B-flat for oboists. So why shouldn’t the bassoon’s low range get a notch down as well, to low A?

And indeed, composers have written low bassoon A’s in their works since the 19th century, assuming that this little ask would be negotiable, even universal. And even the greatest of orchestrator-composers have scored bassoonists into corners, trying to cope with the consequences.

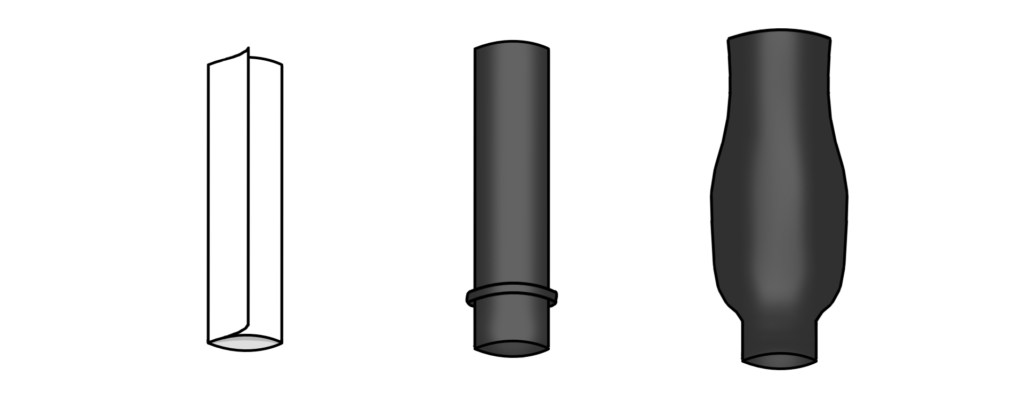

Bassoonists can easily reach A with their instruments, of course. All that’s required is an extra length of tubing inserted into the bell, extending the range of the bassoon’s pipe down another half-step to A1. This extra tubing can be anything from a beautifully machined, purpose-built extension that’s sold along with the instrument, or special-ordered from an instrument builder – all the way to an ignominious sheet of paper rolled up cylindrically and inserted into the bassoon’s bell. Fancy or not, this approach gets the job done – though the player will require fair warning to insert the extension, similar to the time it takes to change from a standard instrument to an auxiliary.

But there’s always a sacrifice involved. The basic problem facing the player is that the bassoon is already optimised for its length to not only provide the greatest degree of expressive control, but also the best possible intonation. It’s that second factor that’s the sticking point. Make the player’s instrument just a little bit longer, and the sense of precise tuning is thrown off. Most pro bassoonists can compensate to a degree, but it’s unwise to score a passage that requires an A extension and yet features any kind of exposed middle and high register scoring. If you want that low A, then keep your scoring in the basement. And even at that, intonation will be difficult, especially on low B.

That’s not to say that “difficult” = “impossible.” Bassoon players and instrument builders have been approaching the problem of intonation. One partial solution is to change the shape of the extension. A bulbous expansion of pipe, similar to an English horn or bass oboe bell, may prove useful in controlling faulty intonation – though it’s at best a bandage and not a cure.

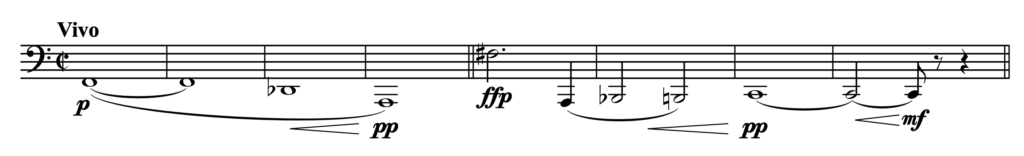

Another bugaboo of A extensions is the loss of the low B-flat note. The key which operates the lowest note of B-flat1 now operates a longer length of piping, correct? So now there’s no more B-flat pitch. This hasn’t stopped composers who really should have known better from asking for an A extension and then assuming a full chromatic range. In passages like the one below, the player has no choice but to drop the low B-flats. Mahler might get away with scoring this, but less-famous composers should avoid such situations at all costs.

On the other hand, some contrabassoons are now built with the ability to play low A – either as a built-in note or with an extension stock. Some players feel that this addition actually stabilises the contra’s intonation rather than harming it. Guntram Wolf’s invention of an improved contrabassoon, the contraforte, is one such instrument. The orchestrator may score low A for contrabassoon from time to time, but the orchestra should be consulted to see whether a contra with a low A is available; and even if it is, an alternate note should be provided in case the work goes on to be played by other orchestras without such instruments.

All this aside, you have to ask yourself as an orchestrator: do you really need that low note? Is it worth it putting the player through all the above just for that extra half-step? Keep in mind as well that as much or even more than any other player in the orchestra (except perhaps for hornists), bassoonists’ sense of self-worth as musicians is tied up in the perfection of their intonation. The A extension may be a small step in pitch, but it’s a giant leap for bassoonistkind.