While the application of extreme dynamics varies widely in musical meaning between composers, eras, and genres, there are some general characteristics relative to the abilities of orchestral players that can be used to forge a systematic approach; giving today’s composers more confidence in scoring these markings.

In my previous tip, “Extreme Dynamics, Part I: Realities and Limitations,” I discussed some of the consequences of using – and perhaps overusing – extreme dynamics. In this tip, I’ll cover how these markings apply to my own philosophy of dynamic balance in the orchestra – and how the capabilities of different orchestral families might interpret each marking.

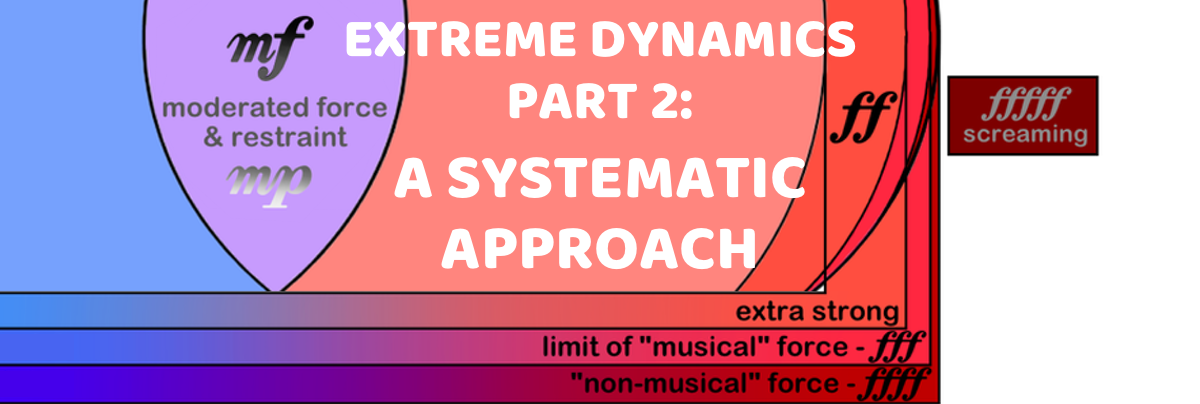

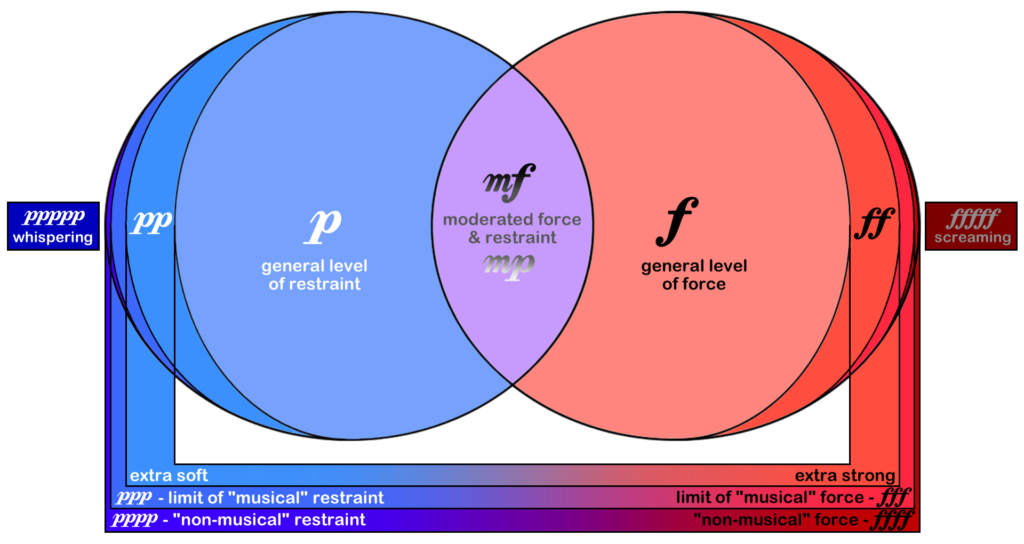

First, a little review. Viewers of my lecture on orchestral balance will know that I pretty much dismiss the concept of the dynamic thermometer, upon which every pitch is a notch representing equal gradations of volume. Acoustic musical instruments do not have faders or volume knobs – and their approach to dynamics is intricately locked together with concerns of intonation, intensity of breath or arm weight, articulation shaping, and cumulative balance within a section or the whole orchestra. Therefore, it’s more useful to talk about dynamics in the context of force and restraint. “Piano” and “forte” are markings that apply to general dynamic levels at which most concert instruments have been designed to sound their absolute best – and these regions should be seen as vast, within which nuance, inflection, and articulation may do most of the work of expressing musical meaning without necessarily having to change the dynamic up or down all that much. Sitting between these two generous regions, mp and mf can be perceived as moderated levels of force or restraint, with somewhat less capacity for ideal expression. While it’s perfectly fine to compose a passage around mp or mf, and even start a composition at those levels, they’re by no means default positions from which the composer should always start their idea and then finish it. Such an approach, at least for concert orchestra, might well result in a duller, less compelling sound (though I will be covering the extensive use of mezzo dynamics in film scoring in a later tip).

I summed up these ideas visually using an earlier version of the chart above, treating the opposing dynamics of p and f as regions in a Venn diagram that overlap in the middle at the mezzo markings. Since, at the time, I was discussing the realities of mezzo markings in the overall scope of orchestral dynamics, I only gave a slight nod toward the placement of pianissimo and fortissimo regions on the opposite edges of the chart. But in this latest version, I’ve included regions of extreme dynamics, more or less proportional to their use in concert repertoire – which is right out to the very edge on either side. But in this tip, let’s start out by pairing up all of the opposing dynamic levels from the middle of the chart outward, comparing them to one another and discussing their realities and consequences when scored. That will help to put the extreme levels into perspective when we get to them.

mp/mf – As I mentioned above, these moderated levels of force and restraint aren’t centred around the most expressive sound of orchestral instruments. They’re very useful in contrasting passages proportional to one another – such as a passage of mf in anticipation of a stronger outpouring later on; or mp used to warm up a softer passage without putting too much of an edge on it. Some composers argue strongly against the use of mp at all; and while I don’t apply the marking all that frequently myself, it does have its uses. But mf is ubiquitous – so much so that developing composers seem to see it as a safe place to hang out most of the time, taking a lukewarm approach to ideas potentially rich and full-bodied at f. My advice: commit to real strength or gentleness rather than diluting your ideas all the time. Which leads us to…

p/f – These very simple, plain markings should serve as the opposing centres around which your scoring finds its most ideal range of expression. Each marking compasses a vast depth of possibility. They’re like separate countries, with main roads, side-tracks, areas of interest, and subtle shades of colour and nuance. A wealth of meaning and emotion can be imparted at these levels, simply by understanding each instrument’s expressive capabilities and bringing them to life with contrasts of register, musical motion, phrasing, and articulation – all before a single hairpin is marked. Each nuance and inflection may further mine the dramatic possibilities, keeping the players right in the sweet spot of their best sound, without pushing them to either suppress or exaggerate the emotion. Always think before you double the dynamic. But when you do…

pp/ff – Think of these markings as “extra soft” and “extra strong.” Just as p and f are general domains of force and restraint, pp and ff represent good general borders. They represent levels at which richness of tone and flexibility of nuance may still play a substantive role. Many of the most bombastic works in the repertoire, notorious for emotional excesses, remain safely within these boundaries, using the combined mass of instrumental strength and quality of tone to do all the heavy lifting that goes into building a towering tutti – or by contrast, reducing string and wind numbers in very soft passages rather than marking anything lower than pianissimo. There’s a lot to be said for maintaining a maximum of control for your players at the emotional extremes, rather than sending them out to the edge of what’s possible. Speaking of which, though…

ppp/fff – As restrained or as forcefully as an instrument can play “musically.” By musically, I mean without any loss of control, danger to intonation, or absence of nuance at fff – while at ppp, all the qualities of timbre and tone formation that define the instrument are still in evidence. ppp is usually what developing composers intend as a fading-in or -out point when using niente hairpins. The difference is that, as we’ll see in the next paragraph, while a true niente is only possible from a limited range of instruments, ppp should be equally playable by ALL orchestral instruments. That doesn’t mean that they will all balance perfectly – see Schoenberg’s Farben for reference – but they can all tone down to a hauntingly subtle softer-than-soft level without the need to add yet another p to the end of the ppp marking. This dynamic is great for taming horns and heavy brass to balance beautifully behind pp winds and strings in a delicate texture. By the same token, fff can give those same winds and strings a fighting chance in a massive tutti over ff brass and percussion, especially in crossover scoring. I’ll cover these balance issues in a future tip. But there’s one big difference. Most instruments can play ppp all day long if the pitches are placed in a comfortable register – for most winds and brass, not too high or low (string players’ arms, though, can grow tired after many many bars of soft, slow bowing on long held notes, limiting their range of motion). But fff has a limited lifespan. Embouchures wear out, arm muscles spasm after too much furious string tremolos, and so on. It’s an extremely powerful weapon in the orchestrator’s arsenal, which is all the more reason why it shouldn’t be used against the players themselves. And just as much as the players wear out, so does the audience in a live concert hall performance. fff can exhaust your listeners emotionally, draining them of any further enthusiasm for your next brilliant idea. A score that goes on for too long at fff is similar to a social media message that’s written in all-caps: REALLY OVERSTRESSING THE POINT THAT THE WRITER IS TRYING TO MAKE TO THE READER. In the same vein, passages that go on for a very long time at ppp may end up having an innocuous, apologetic quality if there’s no intensifying of dramatic interest. In my opinion, then, the orchestrator should use both ppp and fff judiciously; as occasional amendments of pp and amplifications of ff rather than an end in themselves all the time. Of course, I’m suggesting this approach in the context of thematically-based concert scoring, rather than more experimental directions – but no matter what the idiom, players will still have physical limitations. Which brings up the next topic…

pppp/ffff – As restrained or as forcefully as an instrument can play a usable tone “non-musically.” Yes, such playing often requires musicianship of a very high order. But at these extremes, the orchestral player’s carefully-cultivated quality of tone may start to go out the window. A note at pppp may sound so subtle that it’s difficult to tell which instrument is playing – or so intense at ffff that there’s more crudity at play than nobility. There are also limits of usefulness and balance at these points. I would characterise pppp as a niente tone – what Berlioz calls “presque rien” in Symphonie Fantastique. There are very few instruments capable of realistically playing at this extreme: clarinet family instruments; flute family members (especially in their lowest registers); subtones on saxophones; bowed and soft-malleted percussion; string instruments; and middle-register muted brass. But the ability of those instruments to take their dynamic down to the finest of fine points does not mean that any and all of their pitches will balance with one another. The orchestrator must paint with the most delicate of brushes. And let’s be clear about this: the usefulness of this kind of playing is in forcing the audience’s attention down to observing the slightest detail, the merest whisp of tone and musical motion. The kind of effort and focus taken by orchestra members playing so softly should never be taken for granted in my view. I cannot think of anything more discourteous than to have them put an enormous amount of effort into carefully working out the balance and restraint required at pppp, only to have the composer carelessly distract the audience with a heavy foreground element that blots out any trace of them. Tim Davies has some great insights [link] about the scoring and recording of niente in film music. The reverse, ffff, bears twice the physical penalties of the aforementioned limitations of fff for the players – with the added consequence that timbral control, note shaping, and dynamic flexibility are all sacrificed on the altar of sheer volume. A tendency toward a massive blockiness of articulation and tone dominates, basically just turning on and off the loudest level of useful playing. Please keep in mind that you are pushing your players to the absolute limit before essential factors like intonation start to break down. Realities of balance also apply. Brass bellowing away at their loudest will pretty much wipe out the rest of the orchestra, except for the percussion section. At the end of Mars from The Planets, the ffff heavy brass and timpani play with such overwhelming force that Holst doesn’t bother scoring any horns or winds alongside them; and he brings in the strings only where they’ll add a little weight and colour to the low end (if they’re heard at all). If fff is a powerful weapon, then ffff is like the nuclear option. Really be careful how you use this sledgehammer, especially in proportion to the overall scope of expression throughout your entire score. It’s better for it to really mean something important – rather than appearing so often that it loses all sense of tantamount impact for the players.

ppppp/fffff – Whispering or screaming – literally. When we whisper, we reduce or eliminate the vibration of our vocal cords, leaving little behind save for the elements of pronunciation and a hissing sound of breath from our throats. When we scream, we’re using our vocal mechanism to produce the loudest sound possible with few if any considerations of sound quality or clarity. And so it is for the orchestral musician. What’s the point past niente? For the string section, it’s the whispering effect of bows sliding across strings producing little to no tone. For winds and brass, it’s air effects, just the breath blowing through the body of the instrument. And even if the composer expects some kind of perceptible pitch, the risk is that the tone production mechanism will start to melt away. For percussion, it’s even more subtle – like the soft drumming of fingers on a school desk, highly localised and questionable in projection. Some sound may come through, but how much? There may be an element of chance here, especially if you’ve just worn out your players’ arms or lips with many pages of bashing through fff and louder. And if that’s the case, then it may take several bars for the audience to notice the almost silent sound after such huge scoring, and they may think the piece is over and start to clap. Then there’s screaming. Forget about exact intonation, precision, or any kind of shading of colour or nuance. Your players have become a blast furnace of sound, with a tone that’s almost comical in its vulgarity rather than awe-inspiring. We’ve gone beyond mere nuclear options, as fffff is the Death Star of dynamic markings. Utilising this planet-killer of a dynamic requires eight times the caution and judgement of fff. If you use it only once in a career, that may be one time too many – so really REALLY watch out!

Of course, this scale cannot apply to past works in which composers had different notions of dynamic degrees. To make matters even more confusing, many instruments have evolved to a markedly stronger capability since the dawn of the Romantic Era. It’s quite possible that our idea of ff today might sound more like fff to Berlioz. Or he might interpret my description of a niente pppp as pppppp. It’s hard to be sure, as he would mark “presque rien” on different string parts with different markings, one at ppp and the other a mere pp. Other composers like Tchaikovsky seem to imply in their scoring that adding an extra p or f is more of a very slight adjustment of power rather than a definitive step up or down to a clearly defined, independent dynamic. Many other scores reveal different, distinctly logical (or idiosyncratic) approaches to scoring at the extremes. However, I feel that the chart above reflects the experience and perspective of a lot of section players, and boils things down to a logical starting point from which composers can build their own unique concepts of dynamics, balance, and contrast in a passage of music. Remember, only you can ultimately construct your own sound and approach, and a lot of that is built on how you deal with subtleties. But use what you can from this on your way to that point – and always remember that the ultimate decision of assigning proportions lies with the conductor and the musicians.