EVERYTHING YOU DON’T NEED TO KNOW (BUT MAYBE SHOULD) ABOUT HORN BUMPERS

If you were to ask the average seasoned horn player if there’s anything a composer needs to know about bumping, they’ll almost invariably tell you “No. That’s not your concern in any way. Leave that decision to us.” And yet with all respect to my friends in the horn section (to one of whom I’m married), I’d argue that a composer should at least understand why horn bumping exists and how it works, because knowing this information will deepen your understanding of horn playing.

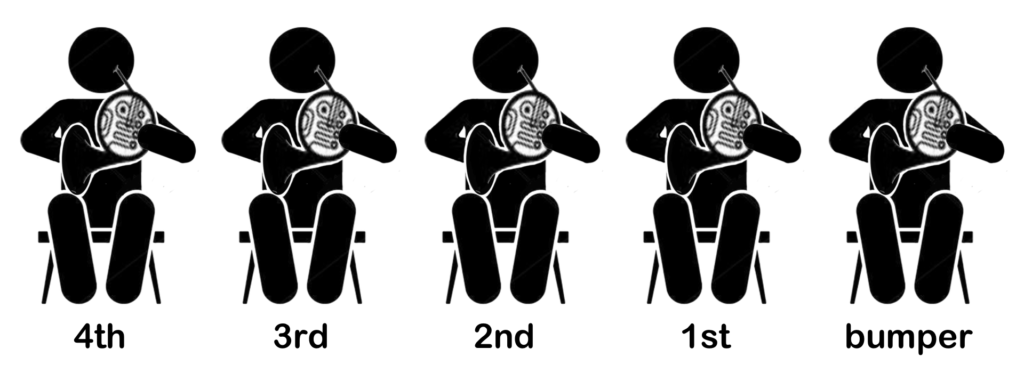

What is a horn bumper? For some performances, an additional hornist will be engaged to serve as an assistant to the first horn player, to “bump” their playing. This player sits to the first’s left side, and shares much of their part according to the needs of the first player. If you’ve ever attended a concert with five hornists onstage playing a symphony by Tchaikovsky or Shostakovich, then you’ve seen a bumper at work alongside the normal quartet of horns. I recommend watching the bumper and the first player closely in these cases to see when one or the other plays, and for when they both play.

No other first player in the brass section (or any other section) benefits from this kind of extra hired assistance, whose presence is absent from the score but oh-so-welcome during the performance. This is because not only is the horn possibly the most physically difficult instrument to play in the orchestra, but it also has parts written for it that require the players to go to the opposite extremes of their technique, many times within the same work. For the player with the greatest responsibility – the first – maintaining a degree of world-class excellence from delicate soloing to ferocious section playing may be impossible without some kind of assistance.

To understand why, try an experiment. Hang by your fingers like a rock climber for as long as you can, really letting the fingers take the entire weight of your body if possible. You can try a tree branch, monkey bars, or even a real rockface (no liability is assumed by the management for sore fingers, or heaven forbid falling off). Then as quickly as possible, do something elegant and painstaking with your fingers, like playing a Chopin piano nocturne, knitting, or writing calligraphy. Even just attempting cursive handwriting will show you right away that the two different uses of the same muscle groups aren’t compatible, and require a period of rest before going from the first to the second.

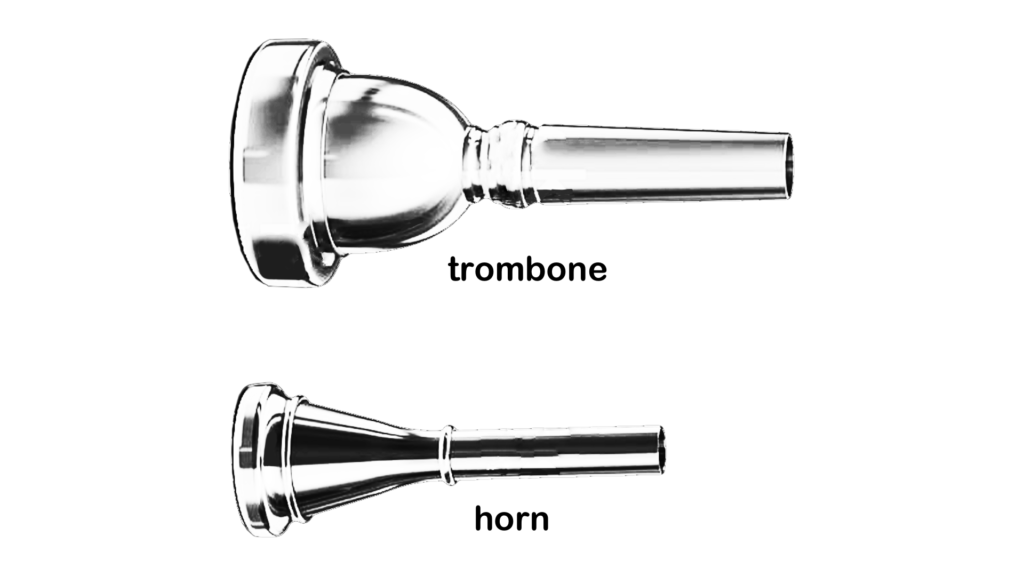

Now consider the challenges facing the concert hornist. The muscle group that forms their embouchure is quite narrow compared to other brass players proportional to the range of pitches available. While today’s standard double horn has essentially the same range as the tenor trombone, just compare the solid, generous aperture of the trombone’s mouthpiece to the delicate little flared cone of the horn. That means that the very centre of the hornist’s lips are going to be shaping a phenomenal range of colours and intensities of timbre, from a piercing high C (sounding F5) going all the way down to a blustering concert G1. Just like every other brass instrument, the range of muscular control narrows to the extreme when playing very high notes.

The finger experiment mirrors the difficulties the horns are confronted with during a performance. It’s essentially the same quandary that a first hornist might face in very high, intense playing (hanging from one’s fingetips on that high C) followed by delicately sensitive playing (like performing tricky surgery). And it’s not just needing a little rest before playing a solo after a few high C’s. The longer a hornist engages in forceful playing, the more they exhaust their control of graceful nuances. When a conductor insists on the full range of both power and sensitivity from their horn section in a demanding work, then it’s time to call in a bumper.

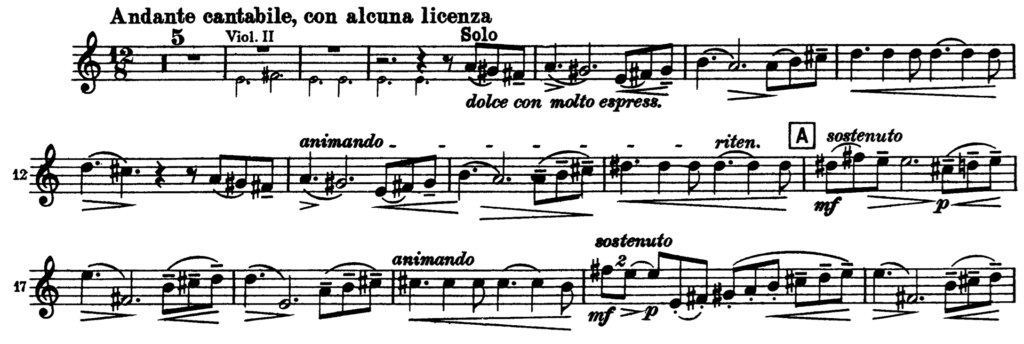

There are three essential roles a bumper may play. Most commonly the bumper substitutes for the first player during certain physically taxing passages, so that the first can save their lip for a more delicate bit of solo work. A bumper might end up covering for the first quite a bit, even playing most of the section work of an entire first movement if the second movement is replete with extended solos. Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony provides a classic example, with its over-the-top opening Allegro movement followed by the most generously tender Andante.

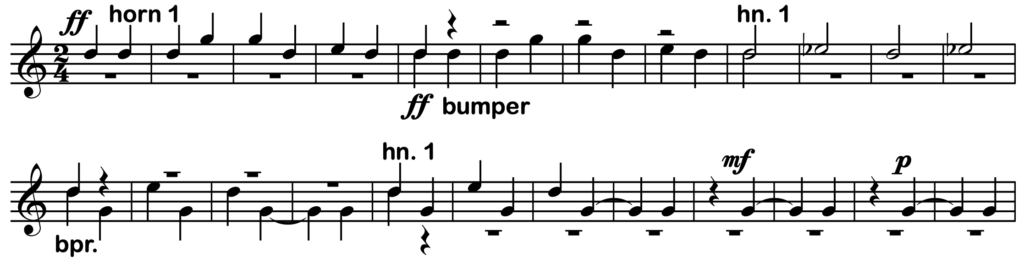

This is not to say that a first never plays anything but solos if they have a bumper. Far from it. Their role as leader of the section is, if anything, strengthened by the assistance of the bumper. They’ll still contribute quite a bit to the overall part, it’s just that they can take a break during sections that don’t require their direct leadership. Quite often, they’ll team up with the bumper to reinforce the top pitch of a harmony or a tutti melodic line. This is the second common form of bumping. Specific articulations, especially accents on the downbeat, have a lot more punch with two players. This makes the first’s job a lot easier in bringing emphasis to the top of the section where the effort is the most demanding. The ultimate result is a better sound quality with less strain.

The third main responsibility for a bumper is trading off with the first in tutti passages with the kind of loud playing that uses up a lot of breath. The two players may dovetail seamlessly back and forth between groups of bars, giving each other much-needed breaks for air and rest. If the first and their bumper are really in tune with one another, this kind of alternating playing can sound seamless. In fact, you’ve probably heard a lot of this on great recordings without even realising it.

Let me reinforce the conviction of pro horn players that this is nothing you ever need to worry about as a composer and orchestrator. Don’t ever assume you’ll be telling an orchestra to get a bumper for your piece – and even more so, don’t ever write a bumper part into your score. Your trusty horn players have got this covered, and a bumper will be hired if there’s a real need (not to mention the budget). On the other hand, some first players have lips of iron and will either play everything the bumper does anyway, or blast their way through huge symphonies and operas without any bumper at all.

All the same, there’s still one relevant takeaway for composers. If you’re scoring for orchestras with smaller budgets and/or more semipro players, then in all likelihood a bumper will not be available. So if you write works that really require the first to play a carefully nuanced solo two bars after a run of fortissimo high C’s, then that player has no escape valve. Practically speaking, you’re asking the player to sacrifice one section of the music on the altar of the other. The same thinking could be applied to the other two jobs of the bumper, in perhaps writing many many bars of loud high playing that simply wear out the player without their wingman, or lots of long exposed notes that can’t be dovetailed.

At the beginning of the tip, I suggested that you should watch how a first divides their parts with their bumper, should you ever see them at work together. In concluding this tip, I’d go even further in suggesting that you take notes and then score-read those works after the concert, to see how the composers are asking more from their firsts than may be humanly possible if the player is to maintain the highest level of excellence. Then really think about how you’re scoring your horn parts for the kind of players you’re commissioned to work with. It may make all the difference between a happy horn section of players performing your music brilliantly, or a tense group of hornists hoping just to get through the performance without any huge disasters.

For more about horn bumping from the player’s perspective, read this great article from hornist Jonathan West’s “Horn Thoughts” blog.

http://jonathanhornthoughts.blogspot.com/2010/11/about-bumping.html