The orchestrator should learn to automatically envision what type of bowing is to be used in every orchestral passage, and mark those passages as needed.

This is one of those steps on the road to mastery for a professional orchestrator – learning all the different types of bowing, and indicating the appropriate style in the score. But not just putting in the words; rather, knowing with certainty that your marking will be the right thing to do at that point. It’s the mark of a composer at the beginning of their development to leave these markings out – often, to leave out any kinds of slurs or even dynamics. Surprise your orchestration coach by learning all about them and putting them in.

In my orchestration video series that I’ve been scripting recently, I called the violin “the basic building block of the orchestra.” Then I went on, “All the other members of the strings section are either constructed along its model, or adapted to its parameters.” I’m noticing that a lot of early efforts are obsessed with grandiosity, or with the more percussive, motoristic possibilities of orchestral scoring. Well and good. But the greatest, grandest, and most propulsive music in the repertoire was orchestrated by composers who knew their stuff about strings. No matter how wild the music may be getting, the strings know exactly what to do so their efforts aren’t wasted.

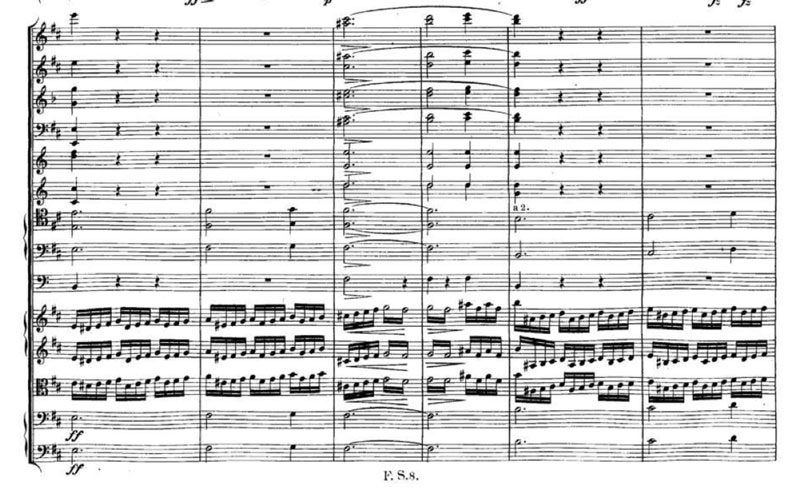

In the excerpt below, from Schubert’s “Unfinished” Symphony, movt. 1, the violins and violas are playing a passage of 16th-notes at ff with no slurs. If a beginning orchestrator composes such a passage, are they aware of the consequences? What will it sound like? In this case, the violins will be using a specific type of bowing called detaché. It’s not a legato, and it’s not a staccato, but somewhere in between. The bow will be placed at center of its span, and moved briskly back and forth. Keeping the bow centered keeps the tone even, and agility at a maximum.

This passage could be interpreted so many different ways. If the marking were pp instead of ff, the players might use the tip of the bow, called “a punta d’arco.” It could also be played with the bow bouncing back and forth off the string, called jeté bowing. And if Schubert was really trying to be excessively ferocious here, he might mark the passage “al tallone,” using the heel of the bow exclusively.

But since none of these markings are indicated, and no slurs are written in, the players automatically play detaché. That is the big point here – the absence of a mark is also a kind of mark. It’s the character of the music that dictates the bowing style. The composer should be completely aware of the implications.

One response to “Strings – Bowing Styles and Markings”