(Tip no. 68 from 100 MORE Orchestration Tips)

The reasons why xylophone can hold its own in an orchestral tutti and a marimba can’t are literally carved right into the instruments.

Similar to some previous tips, here’s some information about mallet percussion that didn’t make it into 100 Orchestration Tips. Sometimes, really understanding an acoustic phenomenon helps a composer to make the right decision in scoring, and leads to a deeper understanding of the instrument. In this case, there’s the odd phenomenon of xylophone versus marimba. Both are made of wooden tone bars. What makes one so bright and the other so dark. Why is it that the first instrument can ring out easily against massive orchestral textures while the other disappears quickly into a mf cushion of winds and strings?

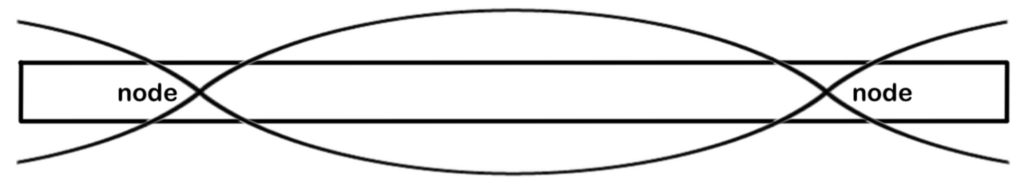

The answer lies in the mathematics of idiophone construction. Don’t get scared by that technical-sounding sentence, I’ll skip the actual math. An idiophone is an instrument that produces sound by vibrating through its solid mass. This is vastly different from any other instrument that uses a string or a column of air in a pipe. Mallet instruments are mostly constructed of tone bars which set up a waveform between nodes near the opposite ends of each bar.

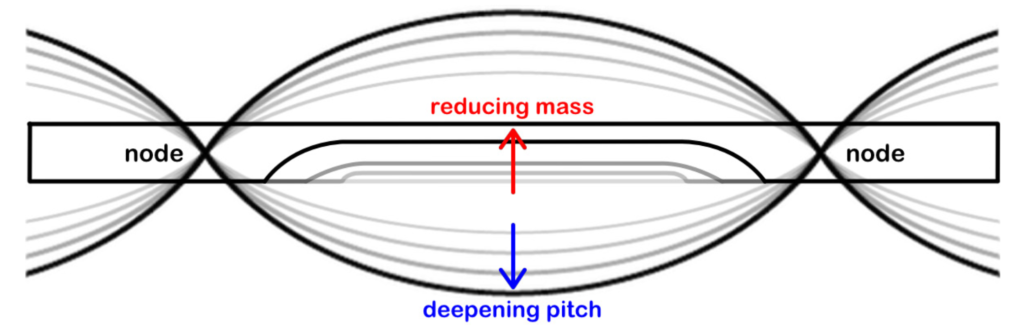

The size needed for a solid bar of wood to play deep tones can get to be enormous. Fortunately for percussionists and instrument builders, there’s an easy solution. Reducing the mass in the centre of a bar deepens its pitch. This area is called the “antinode” as it is positioned halfway between the nodes. This is the reason why the underside of mallet instrument bars are carved out, sometimes just by a small notch to exactly adjust the pitch, or deeply gouged out for a lower sound. While a waveform between two fixed nodes cannot get any longer, it can get wider – similar to tuning a guitar or violin string down.

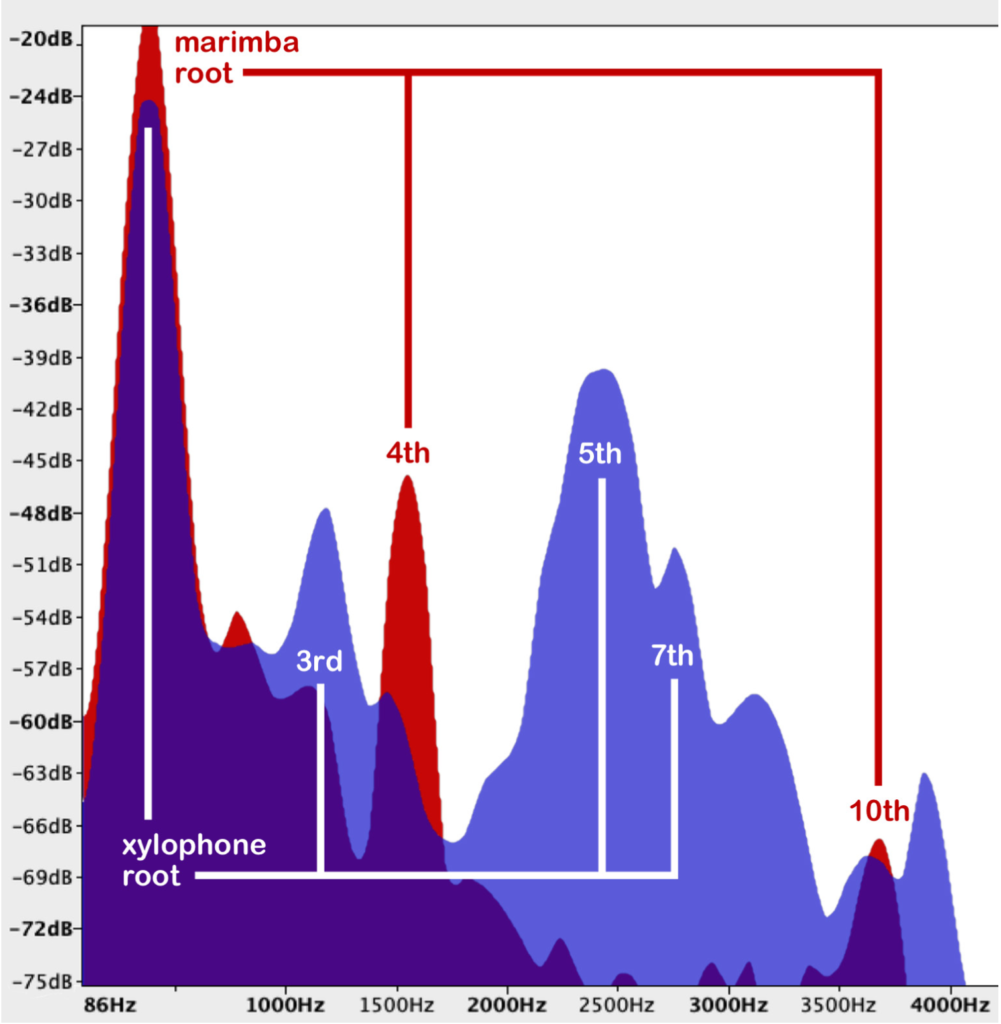

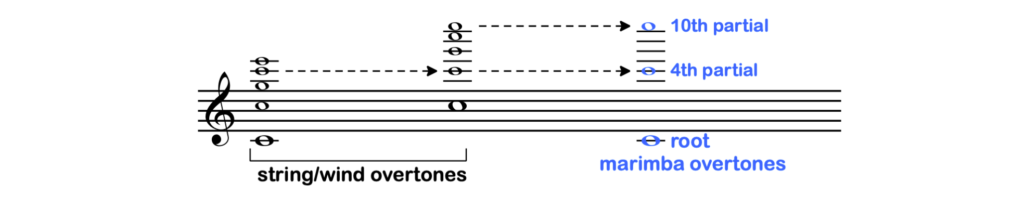

You may have already realised what’s going on here: an idiophone’s overtones can be adjusted by reducing mass between its nodes. So part of a percussion instrument builder’s job is to fine-tune the harmonics of each tone bar further, and this is what gives each mallet instrument its unique character. Marimba tone bars are carved to favour the 4th and 10th partials, sounding two octaves and three octaves plus a major third above the root tone. These overtones are very similar to the strong 2nd and 5th partials of string and wind instruments (excluding clarinet), especially double reeds, but cannot compete as these partials are so high and so much more subtle. This is one reason why the marimba’s timbre is so easily swallowed even in moderate orchestral scoring.

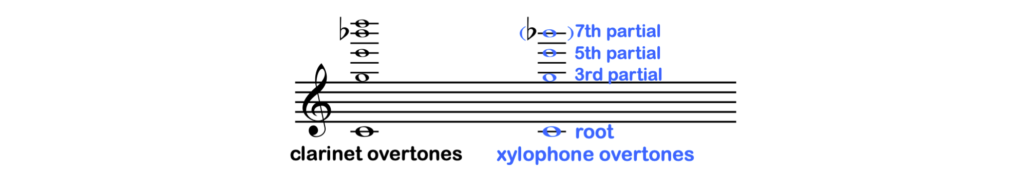

The xylophone, on the other hand, is tuned more like a clarinet. It’s been carefully carved to favour the 3rd partial, only an octave and a 5th above the root, resulting in a more cutting, ringing tone. In fact, it conveys all the brightness and intensity of the clarinet’s clarino and altissimo registers for the same acoustic reasons. Precisely because it does not line up with the general trend of overtones in most of the rest of the orchestra, it can chime away with little or no competition.

Comparing the spectra between the two instruments reveals even more interesting features. Xylophone not only has a fairly prominent 3rd partial, but also a powerful 5th partial as well, and a little spike on the 7th. This is once again perfectly in line with the timbral peculiarities of the clarinet. Marimba, while its root spikes a little higher than the xylophone, has less body of tone, and drops away the steepest right where the xylophone gains more strength.