The similarities of timbre between saxophone models and orchestral winds and brass should be well-known to the orchestrator.

When saxophones made their initial orchestral appearances in the late 19th/early 20th centuries, it was for their uniqueness of timbre, introducing what would have been an exotic sound into the standard ranks of the wind section. Despite these promising early beginnings, though, they failed to become a permanent installation, and remain occasional visitors. Part of this is due to lack of interest by most composers, along with the added cost of hiring new personnel on a permanent basis. There’s also the sense that saxophones tend to outplay other woodwinds, or sound too similar to them. I can’t speak to composer trends or budget considerations in these tips; but I can seize on what’s seen to be a problem of orchestration, and show how it’s actually a solution.

The way I see it, the timbral similarities of saxophones to concert winds and brass are a doorway to good scoring habits by orchestrators. One can build on these relationships of sound to explore both contrasts and cohesion between saxophones and orchestral instruments – so long as one maintains a sensible approach with a few caveats.

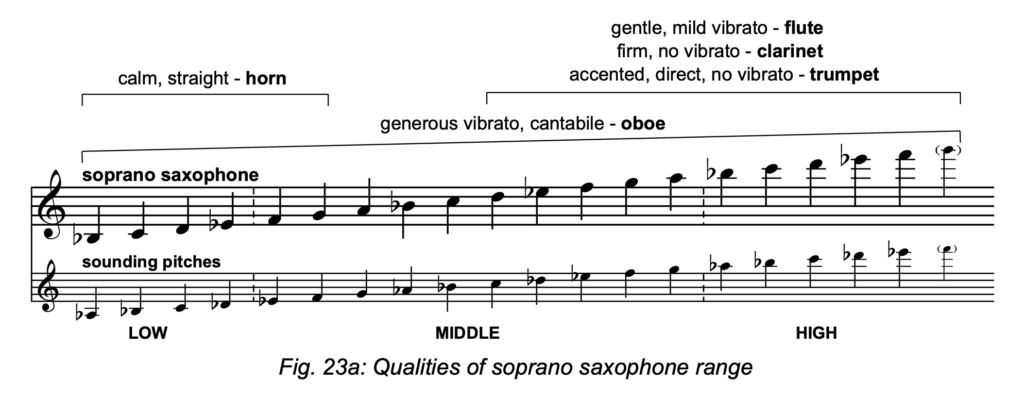

Let’s start by describing the general similarities of different saxophones, limiting ourselves to the most commonly used models for concert music: the soprano, the alto, the tenor, and the baritone. (We’ll also omit considerations of altissimo register playing.) The soprano, I feel, is the model with the most potential for imitation across its entire range. When played very gently with mild vibrato in its middle-to-upper register, it can sound almost flute-like (especially if the player is consciously imitating that timbre). Without vibrato, the same range can sound like a clarinet with a firmer approach, and positively trumpet-like with forceful playing. On the other hand, with generous vibrato and a cantabile approach, most of the soprano’s range can sound very oboe-like.

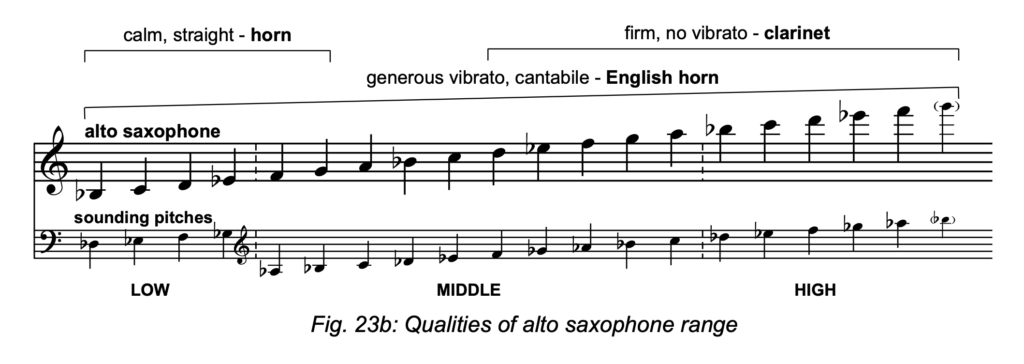

The first orchestra I ever worked with was a semi-volunteer, semi-scholastic orchestra attached to a junior college in Northern California. They often didn’t have all the players they needed, and substituted instruments here or there at times. One such was the English horn, the solos for which were sometimes supplied by a clarinetist playing alto saxophone (the conductor offhandedly called their part “The English Saxophone”). This actually proved quite haunting in their performance of the second movement of Dvorak’s 9th Symphony. Because of the inescapably reedy quality of the alto and lower saxophones, it’s harder for them to approximate (let alone imitate) the timbre of heavy brass instruments. However, similar to the soprano, an alto can sound clarinet-like over the same register, so long as its played without vibrato. And with a cool, straight, non-edgy timbre, it can also sound horn-like over its low register.

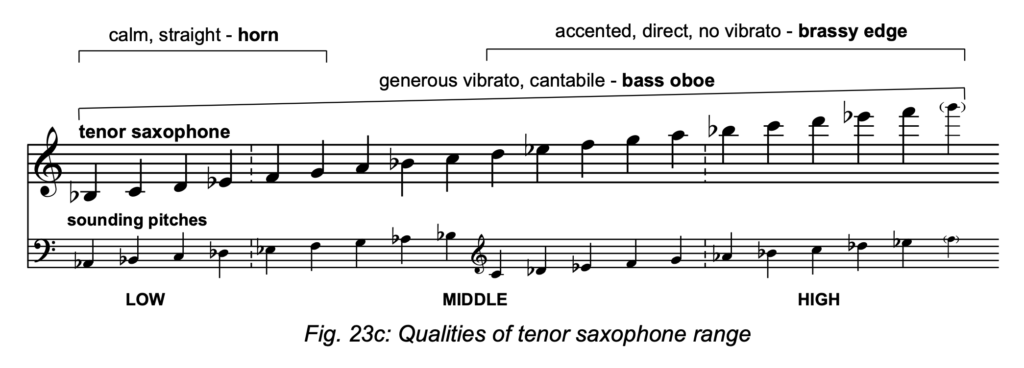

The tenor saxophone is the hardest instrument for which to find parallels, as I feel it has the most individual tone of the saxophone quartet. Its middle register doesn’t quite emulate the tenor registers of lower orchestral instruments. It’s much more generous than the paler tenor of the bassoon, more reedy than the trombone, more gutsy than the cello. The instrument it most resembles, in fact, is another very rare visitor, the bass oboe. The lupophone in particular has a mellow middle register that’s quite reminiscent, though not identical to the tenor. But the tenor can crackle as hard as any brass instrument when pushed, and yet approximate a softly-played horn in its lower register sans vibrato.

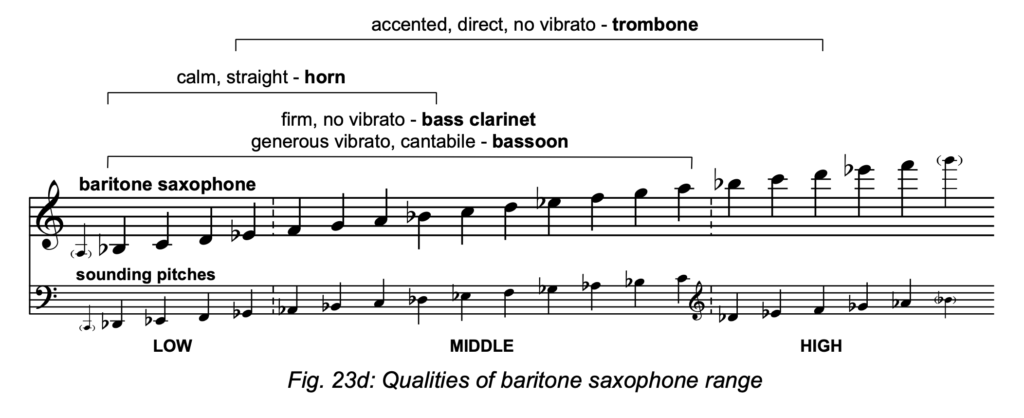

That leaves the baritone saxophone, in which we see the ability to simulate other instruments returning. A baritone played warmly with generous vibrato can sound remarkably like a bassoon, to the point of near-perfect imitation in the low-to-middle registers by a great player. The same range can also sound bass-clarinet-like without vibrato and not too loud. Pushed without vibrato, and that part of the baritone’s range reveals a similarity to trombone, though if anything edgier.

It’s important to remember that these qualities of tone can be subtle resources with which a player can lightly colour a passage; or with focus may strongly bring blatant similarities to mind. Just like other wind players, a professional concert saxophone player may work hard to have a unique and individual sound, or pursue a certain school of playing while adding their own touches. They may in fact try to avoid some of these similarities by mixing many of these aspects rather than bringing them to the surface individually.

We’ll see how all these factors apply to orchestral scoring in Part 2 of this tip.