(Tip no. 24 from 100 MORE Orchestration Tips, to be released in 2020.)

Similarities of timbre mentioned in the previous tip can provide a guide to the saxophone’s use in soloing, substitution, and textural blending.

Despite similarities between saxophones and concert instrument counterparts, it’s important to underline that resemblances are not replications! No matter what quality of another instrument that a saxophone may appear to emulate, in the end it is still a saxophone, and that will be inescapable to the listener. A soprano may sound clarinet-like with no vibrato over the same tones as a clarinet’s clarino register, but there will still be a warmer, more radiant edge to the timbre. A baritone may resemble a bassoon, yet still possess an aggressive, direct quality that goes beyond it.

It is, in fact, these slight differences that can help guide the orchestrator into assigning a solo passage to a particular saxophone. For instance, Ravel chose the alto saxophone as soloist for his orchestration of “Il Vecchio Castello” from Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition – covering a range and in a context that would have worked perfectly well for the low-to-middle registers of the English horn. For the listeners of his day, the unexpected timbre of the alto would have both fulfilled the audience’s expectation of hearing an English horn-like solo – and subverted those expectations with the difference in timbre. Another great Ravel example is in his masterpiece Boléro (“12 minutes of orchestration without music” as he called it wryly), in which early on in his parade of repeated solos, he assigns the second subject to solo bassoon – and then revisits the same material at the same pitch with tenor saxophone. The contrast between similar registers and timbrally related instruments underlines their differences rather than smoothing them over. The ultimate point is that using saxophone to substitute for or replace a more familiar solo instrument should be undertaken with the intention to draw a contrast, not in spite of differences.

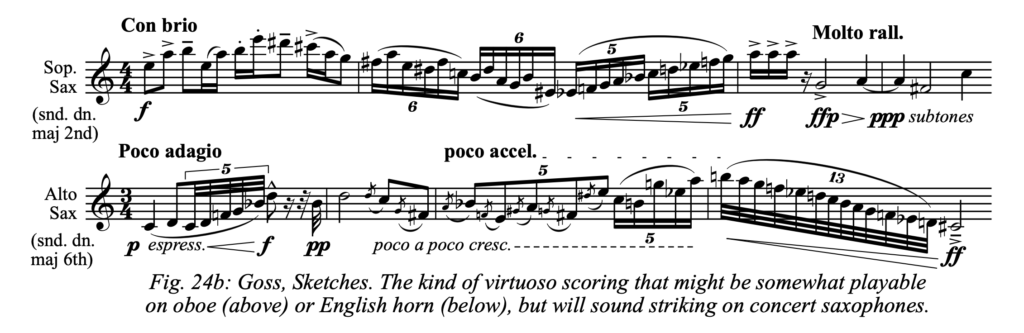

Another good reason to substitute a saxophone for a more familiar concert instrument a concern over agility and dynamic control. If an orchestrator requires the quality of an oboe, but supreme virtuosity and flexibility, not to mention a drop to subtones, then the choice of a soprano saxophone is clear. The same concern might also be remedied for an English horn-like passage with rapid dexterity and clarity required throughout its range.

As much as the above can provide a guide to when to use saxophones, it can also help the orchestrator decide when not to use them. Exposed doubling between a single saxophone and an instrument of similar timbre and range is often problematic, in terms of balance and intonation. It would be better to have these instruments play in octaves than unisons, or in harmony – at least for concert orchestration. As we’ll explore in 100MOT Tip 25, these combinations are often easier to balance with the saxophone as the top element of harmony rather than supporting from below.

However, in tutti textures, these concerns are less problematic. Once again using similarity of timbre as a guide, we can see how saxophones can support their counterparts to great effect over the same pitches and in grouped harmonies, whether in towering tutti chords or more delicately balanced textures.

As I mentioned in the previous tip, alto and tenor saxophones aren’t as directly brassy as the soprano – that is to say, while a soprano saxophone played forcefully without vibrato can simulate clarino trumpet playing, the same exercise with lower models might sound too reedy to bring bass trumpet or trombone to mind for the listener. But of course as most jazz arrangers know very well, saxophones combine beautifully with heavy brass in unison and harmony.* This works best with trumpet as the top voice rather than saxophone, as the latter can get overwhelmed by the overtones and the brass’s projection. This doesn’t have to be jazzy, by the way – such combinations have also been explored in pastoralist and impressionistic concert scoring, from Vaughn Williams to Gershwin.