(Tip no. 2 from 100 MORE Orchestration Tips, to be released in 2020)

Give the solo part to the first player in most cases, whether high or low; and think of the second players’ roles as being supportive in the best way, rather than ignominious.

“To what degree should second wind players should be given solos?” This is one of the most frequently-asked questions – but there’s no way to answer that question without knowing more about the orchestra involved. If, as it is to be expected, a developing orchestrator is working with a student, community, or semipro orchestra, then the question answers itself. Exposed parts for second players should be kept to a minimum, as the difference in technical ability and commitment is at its typically greatest between first and second players in those instances (though not necessarily all the time, which is why you should always try to attend a performance of your client’s orchestra before scoring a single note).

But that’s just the beginning to approaching the overall question of the second wind player’s role (which has a tendency to pass by in one or two brief sentences in the manuals). The deeper the understanding of their role, the better and more engaging the scoring. It’s all too easy for the casual score-reader to breeze right over the strategies and logistics on a crowded page of scoring (with so many often more interesting things happening in the brass and strings) – so let’s bridge that gap with the rest of this tip.

Approach the problem by asking why any orchestral wind instrument requires a second player. When we look through the repertoire, we see many examples of a single wind in a part in which we’re accustomed to seeing two players. Mozart frequently asked for a single flute amongst doubled reed instruments in his symphonies’ wind scoring. Some early Classical symphonies call for a single bassoon to thicken up cello parts – and here in the present, it can be common to score a whole section of single winds in commissions for projects with limited budgets, such as pocket operas and musicals. But consider two factors: length and scope. The longer the work, and the more extensive its colours and dynamic range, the lonelier a single wind is going to appear; whereas a team of two or more players may be far more useful.

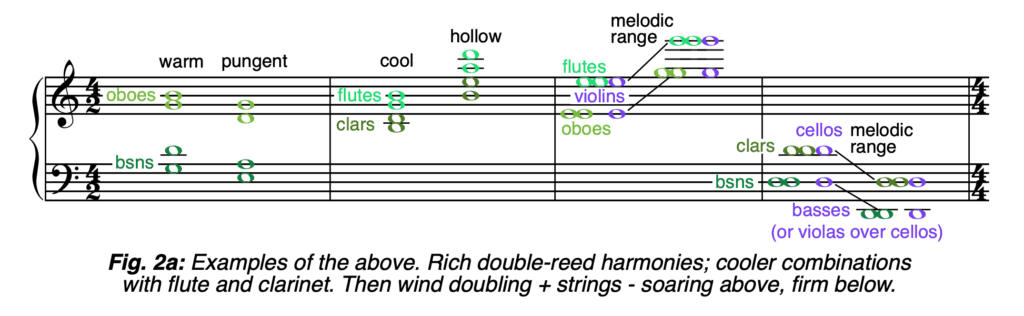

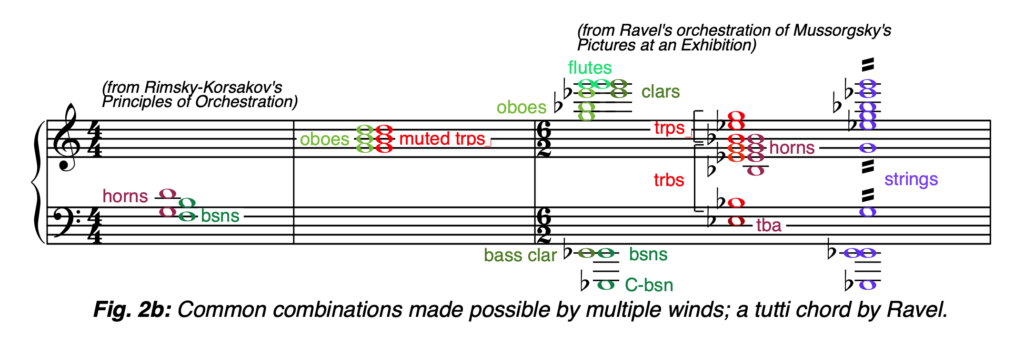

Of course, the advantages are obvious to even the most beginning of score-readers. Doubled winds afford the orchestrator the ability to build harmonies twice as expansive as single winds. This is true both on the titanic-tutti level and in more intimate moments, where a quartet of oboes and bassoons might coordinate in powerfully reedy harmonies; or flutes with clarinets in more hollow, haunting textures. Then there are all those moments when two of the same wind instrument will double up on a single note or line, often in support of soaring melodies or firm bass lines from strings.

To these blatant advantages, I’d also add that more numerous winds can combine texturally with many different orchestral members, not just in their own sections – like bassoons playing harmonies interlocking with horns, or oboes doubling muted trumpets. Also, that if a wind section is composed of eight to twelve individual voices (with or without auxiliaries), then it stands on its own much better alongside the integrated, dominating strings, and the punchy, prominent brass.

So that partially answers the question of what a second wind player is good for: adding harmony to a texture, usually below their first player; and playing in unison. But that’s only the beginning. The second player often adds a touch of support when the first player is soloing. This could be joining in accompaniment and harmonisation, in which the second adds its own timbre to the texture, so that there’s the sound of the instrument in both foreground and background parts. Or the second might harmonise the solo from beneath, hopefully in seamless unity with their first. Finally with regard to supporting solos, the second player (and often third) can take over a leading role in textural or thematic scoring simply to give their first player a rest, before or after or between important solos that may exhaust the embouchure.

Let’s not disregard the second’s role in supporting solos; either as a partner or as a substitute leader. All these roles together often result in the perception that the second is essentially a lower wind player, and the first should always be scored higher. By extrapolation, a developing orchestrator may avoid giving any high parts to the second and any lower parts to the firsts – but that is a mistake. Either player should be equally solid across their entire range.* (A possible exception may apply in the case of double-reed instruments, where the quality of the reeds plays a part in ideal tone formation across registers).

This means that ideally, both first and second wind players should be able to play any sort of solo thrown at them. This doesn’t mean, however, that the orchestrator should spend their career doling out solos to second players in an act of misguided altruism. Exposed soloistic parts for second (and sometimes third) winds are at their best when they interact: dovetailing in and out of fluid lines with the firsts, or responding conversationally with firsts and other instruments with a snatch of theme here or there. While some composers, notably Dvorak, have broken this rule from time to time and heaped solo passages at a second player’s doorstep, it tends to put everyone in an awkward position.

What’s more, in a less formal situation, it can also limit the players available for the orchestra manager if they have to hire what are essentially two first-chair players for every concert. Professional second-chair wind players should be able to step in at any time to cover the first’s part – but you cannot count on that level of experience at the student/community orchestra level. Even some of the better semipro orchestras will contain players who are great second-chair players, but really don’t have the time to study pages and pages of exposed, technically thorny scoring (and let’s not even get into how that might slow down precious rehearsal time for the whole orchestra). Or there may even be some players who have been ensconced into second chair who aren’t that great, but who wield some political clout or seniority, whose skills are better left untested (such stories can be common in community orchestra situations). So the safest option is always to leave extended solos to the firsts, while offering the seconds rewarding, integrated roles.

*This universality of range also applies to brass instruments, but with the caveat that there really are dedicated low players, like third trombone and trumpet, and second and fourth horn.