(Tip no. 3 from 100 Orchestration Tips)

The question of doubling for winds comes up quite often for an orchestrator-in-progress. Strange to say, the simple act of putting two of the same type of wind instrument on the same note can have broad implications for the type of sound you want in the orchestra. You should never do it arbitrarily, or by default. Always question why you want that sound, and be clear about its actual effect on your texture.

This feature of scoring is made all the more complicated by sound sets, especially those specifically created for use in notation software. As of this writing, the words “a2” or “1. solo” have no effect on the sound played back, and therefore may convey nothing to a less experienced orchestrator. And yet the difference is marked at the very least, and sometimes enormous at times.

The first question you have to ask is: why do it at all? The truth is that two wind instruments on a note doesn’t give that note double the dynamic power. It makes the note fuller in terms of projection and tone, but that isn’t volume; that’s tone quality and audibility. And it doesn’t make a woodwind line more expressive to have two oboes or two flutes on it – quite the reverse. The interpretation of dynamic arcs and inflections must necessarily become more controlled and less individual.

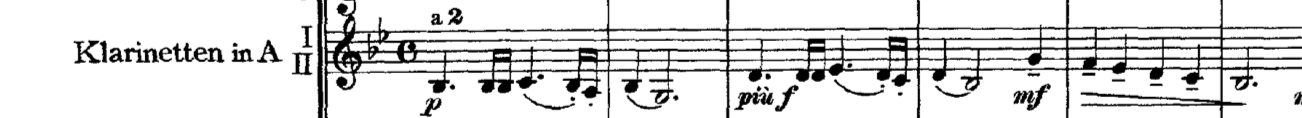

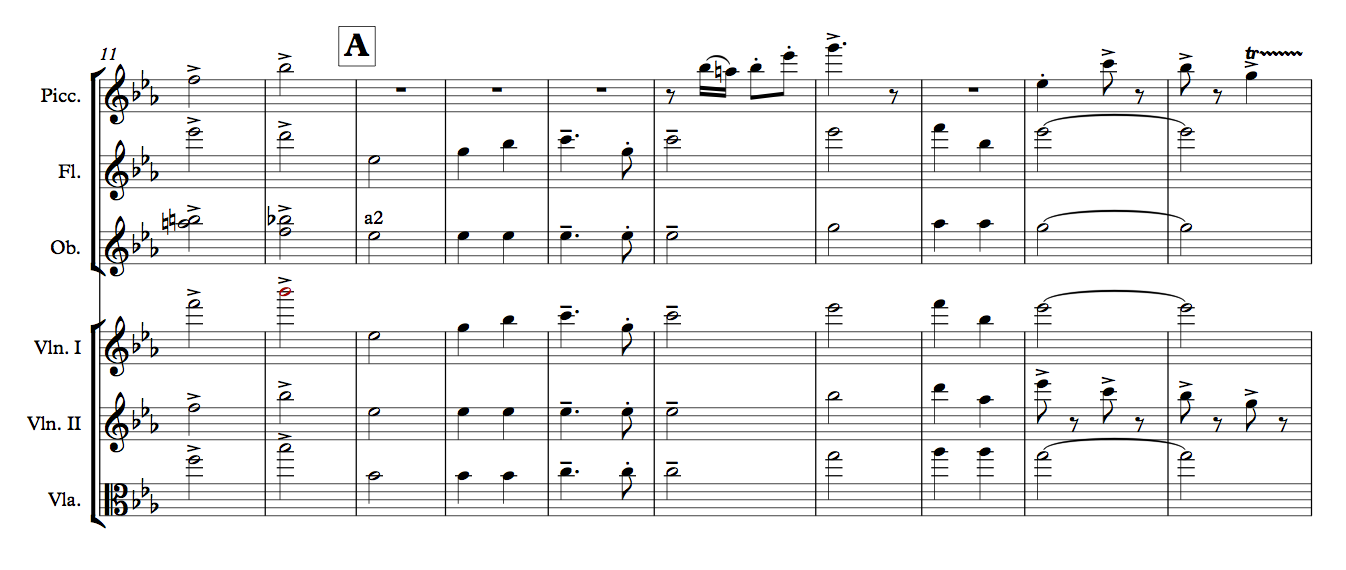

The biggest concern for the players is indeed going to be unity. Players from a topnotch orchestra who sit next to each other for years and know everything about each other’s tone and phrasing will be able to match in a spookily precise way – but few orchestrators have ever counted on this in the wide scope. The reality is that on an exposed melodic part, doubling immediately reveals the minute differences in intonation between the two players. Sometimes this is intentional, as in the famous clarinet solo at the opening of Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony, where the unison of two clarinets ring out coldly in the chalumeau register. A single clarinet here would be much less devastating.

Things don’t get better by merely adding more and more winds. While string instruments sound ever more silky and unified the more you add on one line, the winds have the opposite effect. 16 violins sound unified on a melody – 3-4 clarinets or flutes sound like a marching band, even with excellent players. With amateur players, make that a high school band.

All the same, let’s categorize when such doubling might be appropriate, and what it sounds like when so used. Keep in mind that the following list deals with doubling in exposed parts rather than textural support (which I’ll address at the end).

Doubled flutes – actually, this sound isn’t so bad. Even with good amateur players, one can achieve a nicely blended tone, especially softer and in the middle and lower registers. As a general rule, when wind instruments become ever more strident in tone, the accompanying overtones tend to widen between players – or at least, that’s the perceived effect to the listener as the difference between intonation becomes ever more obvious. This means that the blending for flutes will be quite difficult for the top half octave, especially at fff. Of course, if you’re doing that, you may not care too much about the niceties.

Doubled oboes – this sound is difficult to manage for players in an exposed part, no matter how stable the tuning may be for the instruments. Because of the nature of the overtones, intonation differences can be quite wide, and a line that sounds flowing in the composer’s imagination may have little to do with reality. The worst aspect here is that the precious tone of the oboe is the one that is most cheapened by melodic doubling. And yet this error is repeated over and over, to the consternation of university instructors everywhere.

Doubled clarinets – this can come off a bit better than oboes, because of the essence of the sound. Like Tchaikovsky, an orchestrator can use the somewhat hollow, edgy effect of unison clarinets for a special effect. But it’s important to note that such doubling wears thin quite soon, and should be used carefully if at all.

Doubled bassoons – there’s a wide variety of opinions on this between different orchestrators and teachers. Some feel that such doubling is as tasteless as that of the oboe. Others have little problem with it. My own personal take is that doubling bassoons can work quite well in a bass line, and in the bottom octave and a half of range; but the higher one scores, and the more melodic the part gets, the worse the effect, until finally the sound becomes ridiculous.

Of course, in any such list, there are countless exceptions and variables at play. Articulation can make all the difference – for instance, a row of doubled oboe staccatos might easily come off better-sounding than an attempt at a lyrical melody. And this doesn’t address the question of doubling at the octave, or doubling with other winds, but you can read all about that in Rimsky-Korsakov’s Principle of Orchestration.

One thing is for sure, though – the wonderfully enveloping and forgiving tone of strings can smooth over all differences in intonation, when a doubled wind line is itself strengthening the strings. Here, doubled flutes and doubled oboes can support the melody of first and second violins into the stratosphere, and make them soar with added color and strength. This is especially effective if the winds are playing a hair under the strings in dynamics, or the players take pains to blend. There are other exceptions as well, such as winds stacking in interesting combinations with brass, or winds adding to bits of color in complex textures. The difference here is that the somewhat difficult intonation is less of an issue in the broader scheme; at least that’s true with more experienced players.