My recent experiences in booking wind players for my orchestration course has brought up a very important tip about heckelphone and bass oboe, a factor involved in the use of these instruments that you also won’t find in the orchestration manuals.

I realise, of course, that the two instruments are somewhat different. Heckelphone has a somewhat wider bore and more nasal sound that the bass (aka baritone) oboe. Then there’s also the lupophone, which has an even deeper range and apparently better control than than either of the previous. But whatever the name and exact make, this tip counts for all.

Before the reality, though, here’s the dream: an orchestra in which this tonal resource is readily available, fleshing out the oboe group by providing a solid bass under the English horn. Holst did this in the Planets, even writing a few haunting solo lines for it. Then there’s Strauss’s Alpensinfonie and Salome. Surely by now, massive scoring should have picked up and celebrated the bass oboe, shouldn’t it?

And yet it hasn’t. Certain essential orchestrators never touched it, like Stravinsky or Ravel. More recent massive scoring, especially in film music, has mostly left it alone.

Now my personal opinion is that indeed it is a neglected resource, and would definitely be a welcome ingredient. I’d support the dream of bringing it to a more central position, like the E-flat clarinet, say, or the alto flute. However, I’m all too aware of certain realities that are working against the bass oboe from the very start. Not just that it costs money to hire a player, nor that such instruments are made very expensive due to their rarity. No, the real problems here have to do with fingering, register, and embouchure.

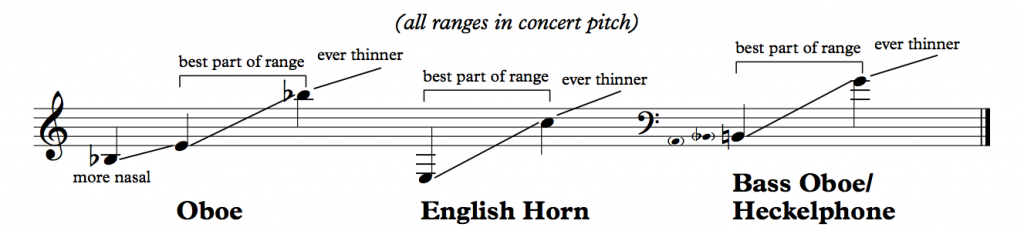

Consider: as you may have read in my previous tips about the oboe, there are certain strengths of range. An orchestral player is going to shape their approach to their embouchure so that the center of the instrument’s range and upward gets the best sound. As the oboe’s range descends, the notes have less and less control, or what some orchestrators would call “quality.”

What this means is that the lowest notes of the English horn, from concert E3-C4, which are considered its best and most characteristic, are about an octave lower from where the best range of the oboe starts – from E4 and upwards. To take it even further, the lowest notes of the Heckelphone are an octave and a fourth below the oboe’s best range. The range may be down an octave or so from the oboe, but those bottom notes which represent the bass oboe at its best happen to be much more than an octave in distance from the very range an oboist may spend his life working on to perfect.

There’s a relationship of breath, embouchure, and control that go along with an orchestral oboe player’s sense of quality playing. The approach needed for a heckelphone is not the same thing at all. The natural strengths will feel more akin to an English horn, with low fundamental tones being the focus.

But the biggest problem is that the bass oboe family is played with much larger reeds. The heckelphone reed is essentially the same as a bassoon reed. This means that as much as a unified section of oboes might be envisioned by orchestrators, the reality is that the bass oboe player will rarely be able to play fourth oboe if ever. And since the bass oboe will be only coming in here and there for textural work or a solo, it’s essentially a wasted resource unless there’s lots of money to throw around. If your work is being premiered the same night as the above pieces by Strauss or Holst, you’re in luck. Otherwise, it’s a very big ask.

Hamish McKeich, a conductor and bassoonist, demonstrating the heckelphone.

The problems don’t end there, though. The bass oboe may have a bassoonist playing it, but it’s no bassoon. The fingering is pretty much that of an oboe. So a player must be picked who either a.) used to be play oboe, or b.) doesn’t mind putting in some hours learning a new system. The outcome very well be weaker than desired, because the player is still learning his way around the instrument.

True, there are some specialist players out there, who are every bit as expert on bass oboe, heckelphone, or now lupophone, as some concert oboists. But these are exponentially rarer than these already rare instruments. Perhaps 100 or so heckelphones have ever been made. The bass or baritone oboe models are less rare. But finding people who can truly play them on a concert music level is extremely difficult – so unless your commission specifically requests the instrument, don’t count on scoring for it in an orchestration any time soon.

Would it be better if the English horn player took on the bass oboe, with one of the regular oboists covering the English horn?