(Tip no. 21 from 100 MORE Orchestration Tips, to be released in 2018)

Score placement is a tricky and evolving thing for visitors to the concert orchestra – especially when that visitor isn’t a soloist, but a general contributor to orchestral texture and function. The saxophone can be particularly puzzling, and not just to developing composers. You’ll find a variety of approaches across the spectrum from established composers since its formal introduction to the orchestra.

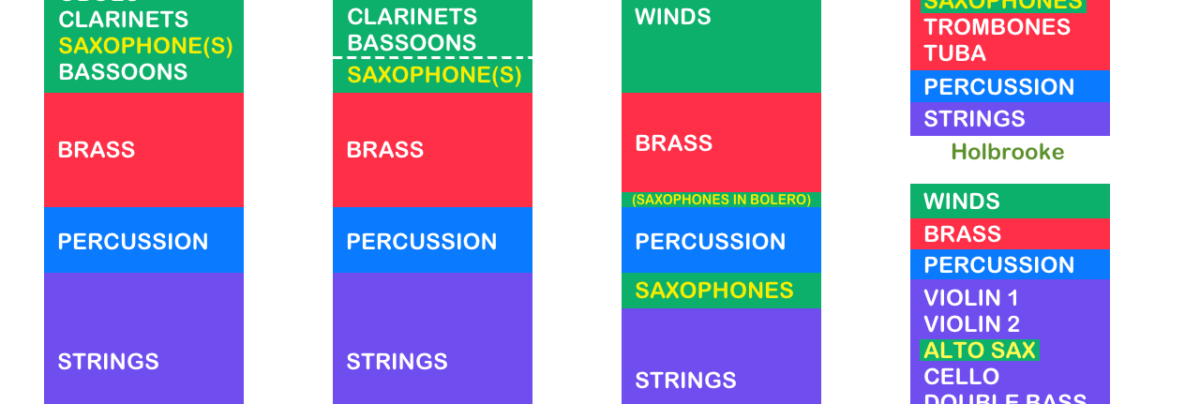

The first successful use of orchestral saxophone is often credited to Bizet. The 1904 Breitkopf & Härtel edition of his suites from L’Arlesienne uses the most common and logical approach to scoring saxophone with orchestra, placing the E-flat alto right between the clarinets and bassoons. There are many other examples of this approach in the literature, such as Prokofiev’s Lt. Kije and Rachmaninov’s Symphonic Dances; so for most scoring, this can be considered the standard. There are two very strong arguments for this placement: first, the instrument is a single-reed, and quite often a tenor or alto, so in range and juxtaposition it makes perfect sense. Second, the instruments have a strong likelihood of being doubled by clarinet players, and so the conductor’s eye will be looking in that direction in conjunction with what’s read in the score.

Of course, this perfect little system tends to be ignored even by composers famed for their perfect orchestrations. Both Ravel’s orchestration of Pictures at an Exhibition and the first edition of Bizet’s L’Arlesienne put the saxophone at the very bottom of the wind section below the bassoons. This may have been an early default approach by French composers and publishers, just adding on the saxophone to its woodwind brethren. Vaughan Williams takes a similar approach in his Symphony no. 9, but separates the barlines so that his added saxophones form their own little group floating below the winds.

The more saxophones are added, the greater the impulse seems to be to put them somewhere else in the score, as if they were their own family of instruments instead of members of the wind section. Such concerns may also address the placement of the saxophones as a featured group of players. This is undoubtedly the case in Gershwin’s score to An American in Paris, where a trio of players cover a variety of alto, tenor and baritone models and are scored on three staves between the percussion and the celesta. Similarly Ravel’s Boleroplaces the sopranino, soprano, and tenor saxes between the brass and percussion, though the actual players were probably intended to sit in the wind section. All the same, it’s worth mentioning that this sense of individuality of function didn’t stop Richard Strauss from placing an entire quartet of saxophones in the standard configuration between the clarinets and bassoons in the massive score to Sinfonia Domestica.

The final consideration in saxophone score placement is timbral relationships, which can be a quite important factor due to the instrument’s flexibility of tone. Holbrooke uses the standard approach in his third symphony, and the French approach in his first. But in his Symphony no. 2, he places his soprano and tenor saxes amongst the heavy brass, between the trumpets and trombones, in fact; and he employs them in quite brassy ways. On the other end of the dynamic spectrum, Milhaud replaces his viola with an alto saxophone in the little cantina orchestra to his ballet L’homme et son desir, with the intention that it functionally form part of the string quintet – nevertheless the balance is hard to maintain in integrated scoring, and Milhaud often has the alto play out in featured lines.

I’ve scored for orchestral saxophone quite often, usually in crossover scoring. I’ve always used the standard approach of placement between clarinets and bassoons. With many working orchestras, the second or third clarinet may well have to switch over to saxophone and back in the course of a single movement. It makes it all the easier for the conductor to keep track of the changeover when the alternate staff is as close to the clarinets as the piccolo staff is next to the flutes. Anything that results in the least amount of confusion is always the best option.