Orchestrators should know the difference between tuba, contrabassoon, and bass clarinet timbre, and score according to each instrument’s strength and character.

This is the kind of tip I love sharing – a comparative look at instruments of similar range and utility, but quite different tone and technique – followed by an excerpt of a favorite moment from one of my own works.

So here are our three deliciously colorful suspects at their simplest description: bass clarinet and contrabassoon as octave extensions of their predominant wind section counterparts; and tuba as a member of its own family, one out of a pack of five options (F, Eb, CC, BBb, or Bb tenor). All three are used most commonly for the bottom note of a harmony or pattern, or to play a bass line. Less often, they will play a solo, or double a featured line with other instruments (typically basses and/or cellos).

First and most practical of comparisons is range. The lowest dependable instrument of the three is the contrabassoon, with a low note of Bb2 (the lowest Bb on the piano). The BBb tuba can also go this low, but rather coarsely, and using this massive instrument has its drawbacks orchestrally. The typical lowest standard note for tuba is up a 3rd at D1 – still a massively low note, to be sure. The bass clarinet’s lowest note was once concert D, but this has been gradually expanded, so that many instruments now extend all the way to Bb1, an octave above the contrabassoon’s lowest note.

Now, just because one instrument goes deeper than another, is not a good reason to use it. Please recall my tips last month about the double bass, and the lack of necessity to use its C-extension. The same thing applies here. As an experienced orchestrator, I rarely ask any of these instruments to hang off the bottom step of their ladder. Parts for these three that are exclusively scored in only their bottom octave are frankly a pain in the tuchus to play, and are often the mark of inexperience. Really, the best part of the range for each of these instruments is similar to the double bass: starting from up a 4th to a 6th from the lowest possible note, to an octave and a half higher. So for contrabassoon, that would be E1 or F1 up to written middle C; for F tuba (the standard), Bb1 up to G in the staff; and for bass clarinet, written low G up to D in the (treble) staff. That’s really where the most function should be happening – not just the lowest possible notes all the time.

This consideration frees us up to consider the character of tone from those ideal ranges – not just the narrow thinking of “who goes lowest?” In terms of flexibility of tone, the ability to blend, and ease of technique, the bass clarinet has got the clear advantage (as well as the widest usable range). It’s superb at discreetly supporting a naked wind texture, blending with lower strings, refining a lower brass line in unison, and many other roles. I see it as the handyman in my orchestrations – patching up a texture here, filling in a loose balance there. But its greatest strength in having a unique solo tone may also disqualify it for certain scoring needs. What’s more, it cannot support the low winds with the same solemnity and lower range as a contrabassoon, nor can it suffice to underpin the brass like the tuba.

The contrabassoon part that has no overall relationship to the bassoons is usually just an unimaginative padding for the lower strings. Of course, contrabassoon terrific at low doubling, don’t get me wrong – but even here, it’s often strongest when it’s playing an octave lower than the bassoons, and both are doubling an octave played by the lower strings. The thing to remember about the contra is that it was specifically built to be the bottom note – and its lowest notes are generally secure, despite my cautions above. And yet these very low tones take a huge amount of breath, and speak very slowly. Another characteristic is a certain weakness of tone – contrabassoon solos must be carefully accompanied, and often have problems projecting over the sound of even a delicate texture.

The tuba has no such problem being heard – quite the opposite. Its tone has a hugely energetic effect on pushing sound waves through a concert hall. It’s much more secure than the contrabassoon in agile passages, and can fill in as bass in a number of different contexts. In fact, I feel much of what’s possible for tuba has yet to be explored, simply because of inexperience with the instrument on the part of even professional orchestrators. That said, there are definitely places where its tone doesn’t quite fit.

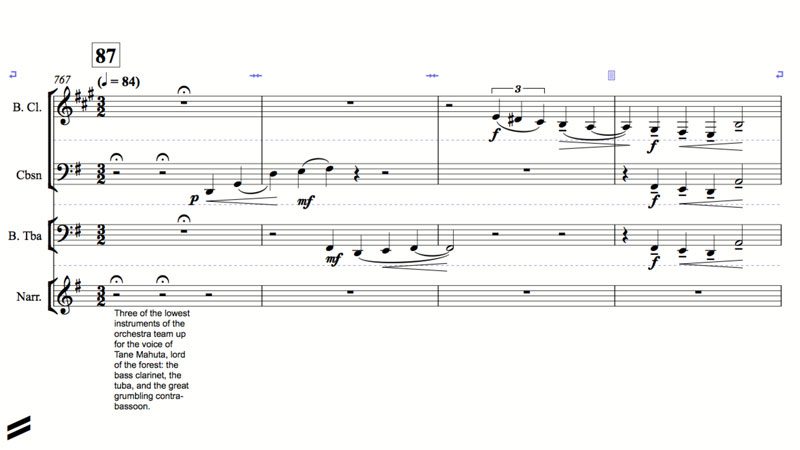

In the excerpt below from my first New Zealand legend for orchestra, “Tane and the Kiwi,” our three suspects are introducing the voice of the god of the forest. Note the scoring here, showing each instrument at its strongest range: the contrabassoon starts off from low E, rising to F in the staff, where it overlaps into the tuba part. This overlap, by the way, is very tricky to pull off convincingly, as the tones are so different – but I’ve been fortunate from both orchestras who presented this piece in many concerts over the past decade. The bass clarinet picks up the phrase from above, as the higher-pitched instrument; then all three finish off with tuba and bass clarinet in unison, with contrabassoon an octave below. The sound from these last four notes is huge – much bigger than I’d get if the tuba and contrabassoon were reversed.

(I haven’t mentioned contrabass clarinet, because I wanted to focus on the commonly-used auxiliaries today, and I’ve dealt with that unique, beautiful instrument elsewhere.)

Is there an audio recording of that somewhere on the interweb? would be great!

Hi Felix!

I wish I could play it for you, or let you know where to buy a CD. The sad reality of this business is that orchestras don’t always have the money to record their concerts, and us composers are honor-bound not to distribute any archival recordings they may have.

But I will let everyone know when it’s broadcast again on Radio New Zealand.